Wheels are all around us. You use them every day,

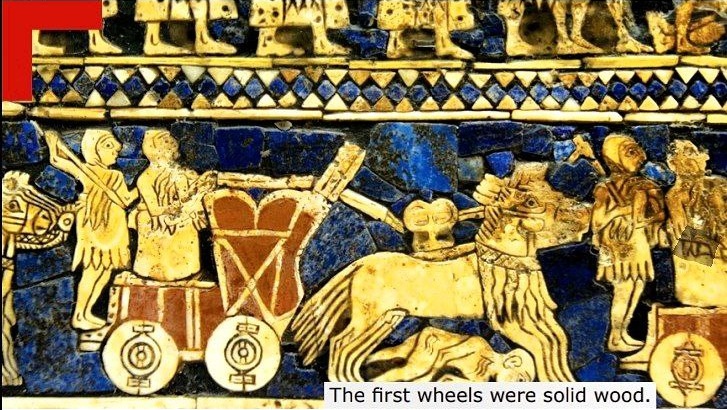

The Sumerians were also credited for the revolutionary invention of the wheel and the plough. They grew bumper crops of cereals, which they traded for items they needed: wood, building stone or metals. Wheeled carts and their skills in writing helped them develop long-distance trade. The first wheels were made of planks of solid wood held together with crosspieces. They were clumsy and heavy at the beginnin. .The Sumerians didn’t invent wheeled vehicles, but they probably developed the first two-wheeled chariot in which a driver drove a team of animals,

writes Richard W. Bulliet in The Wheel: Inventions and Reinventions.

there’s evidence the Sumerians had such carts for transportation in the 3000s B.C., but they were probably used for ceremonies or by the military, rather than as a means to get around the countryside, where the rough terrain would have made wheeled travel difficult.

The Sumerians were also credited for the revolutionary invention of the wheel and the plough. They grew bumper crops of cereals, which they traded for items they needed: wood, building stone or metals. Wheeled carts and their skills in writing helped them develop long-distance trade. The first wheels were made of planks of solid wood held together with crosspieces. They were clumsy and heavy at the beginnin. In time, lighter wheels were made; these had many spokes. The first ploughs were also made of wood with the blade made from bronze.

The earliest evidence of wheeled vehicles dates back to approximately 3500-3300 BCE in Mesopotamia, Iraq These early wheels were not solid disks as we commonly envision them today but rather wooden disks with a hole in the center for an axle. They were attached to carts used for transporting goods, primarily in agricultural and trade activities

The invention of the wheel stands as a monumental achievement in human history, an innovation that has profoundly shaped the course of civilization. While the wheel’s importance is undeniable, the question of who first conceived this ingenious invention remains shrouded in mystery

Who Invented the Wheel?

No one individual, culture, or civilization can take sole credit for inventing the wheel, although the general consensus is that the ancient Sumerians had a hand in it. The wheel is, without a doubt, one of humanity’s most transformative innovations. Its invention marked a turning point in the development of tools and technology, and its influence transcended time and place

The earliest wheels used in Mesopotamia were potter’s wheels, which were used to more efficiently shape clay. To effectively use a potter’s wheel, the potter would require a more elastic clay, which was plentiful throughout regions of Mesopotamia at the time. It is also why Mesopotamia is known for its clay tablets, which preserved much of their history in cuniform. There was just a ton of clay to be found throughout the Fertile Crescent

The invention of the wheel was a watershed moment in human history, but its true impact goes far beyond its origins. As the wheel evolved and technology advanced, it transformed transportation and technology, leaving an indelible mark on civilization in its wake

The wheel’s primary purpose was to revolutionize transportation. It enabled the movement of heavy goods and people with greater ease and efficiency than ever before. In ancient times, wheeled carts and chariots became essential tools for trade, agriculture, and warfare. This newfound mobility expanded the reach of civilizations and facilitated the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures

The adoption of wheeled plows marked a significant advancement in agriculture. It allowed farmers to till the soil more efficiently, increasing crop yields and food production. This surplus food supported population growth and the development of complex, settled societies

Major Technological Innovations

The wheel’s influence extended to other technological innovations. Gears, for instance, are closely related to the wheel and played a crucial role in the development of machinery and clocks.

The principles behind the wheel also contributed to advancements in engineering, leading to the creation of waterwheels and windmills for power generation and agriculture

in ancient Iraq as today, children’s toys were often wheeled

This example is a ram with curving horns on wheels that could be pulled by a child. It has been designed so that the animal rests on two clay axles to which wheels are attached.Iraq, Akkadian civilization (2334-2154 BC)

Our Sources :

History Begins at Sumer (Philadelphia, 1956), Thirty Nine Firsts in Recorded History, by Samuel Noah Kramer, in 404 searchable pdf pages.

Selected Writings of Samuel Noah Kramer, in 570 bookmarked and searchable pdf pages.

Green، M.W. (1981). “The Construction and Implementation of the Cuneiform Writing System

Samuel Noah Kramer University of Pennsylvania Press, 1972 – History – 130 pages

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1944). Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C. American Philosophical Society. Revised edition: 1961.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1981). History Begins at Sumer: Thirty-Nine Firsts in Man’s Recorded History (3 ed.). University of Pennsylvania Press. I. First edition: 1956 (Twenty-Five Firsts). Second Edition: 1959 (Twenty-Seven Firsts).

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1963). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character Samuel Noah Kramer (PDF). University of Chicago Press.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1967). Cradle of Civilization: Picture-text survey that reconstructs the history, politics, religion and cultural achievements of ancient Sumer, Babylonia and Assyria. Time-Life: Great Ages of Man: A History of the World’s Cultures..

- Wolkstein, Diane; Kramer, Samuel Noah (1983). Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer. New York: Harper & Row.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1988a). In the World of Sumer: An Autobiography. Wayne State University Press

- Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization. Paul Kriwaczek.

Ancient Mesopotamia. Leo Oppenheim.

Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History. University of Chicago.

Mesopotamia 8000-2000 B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

30,000 Years of Art. Editors at Phaidon. - Treasures of the Iraq Museum Faraj Basmachi Ministry of Information, 1976 – Art, Iraqi – 426 pages

- Algaze, Guillermo, 2008 Ancient Mesopotamia at the Dawn of Civilization: the Evolution of an Urban Landscape. University of Chicago Press

- Atlas de la Mésopotamie et du Proche-Orient ancien, Brepols, 1996

- Bottéro, Jean; 1987. (in French) Mésopotamie. L’écriture, la raison et les dieux, Gallimard, coll. « Folio Histoire »,

- Edzard, Dietz Otto; 2004. Geschichte Mesopotamiens. Von den Sumerern bis zu Alexander dem Großen, München,

- Hrouda, Barthel and Rene Pfeilschifter; 2005. Mesopotamien. Die antiken Kulturen zwischen Euphrat und Tigris. München 2005 (4. Aufl.),

- Joannès, Francis; 2001. Dictionnaire de la civilisation mésopotamienne, Robert Laffont.

- Korn, Wolfgang; 2004. Mesopotamien – Wiege der Zivilisation. 6000 Jahre Hochkulturen an Euphrat und Tigris, Stuttgart,

- Matthews, Roger; 2005. The early prehistory of Mesopotamia – 500,000 to 4,500 BC, Turnhout 2005,

- Oppenheim, A. Leo; 1964. Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a dead civilization. The University of Chicago Press: Chicago and London. Revised edition completed by Erica Reiner, 1977.

- Pollock, Susan; 1999. Ancient Mesopotamia: the Eden that never was. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- Postgate, J. Nicholas; 1992. Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the dawn of history. Routledge: London and New York.

- Roux, Georges; 1964. Ancient Iraq, Penguin Books.

- Silver, Morris; 2007. Redistribution and Markets in the Economy of Ancient Mesopotamia: Updating Polanyi, Antiguo Oriente

- Pingree, David (1998). “Legacies in Astronomy and Celestial Omens”. In Dalley, Stephanie (ed.). The Legacy of Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press.

- Stager, L. E. (1996). “The fury of Babylon: Ashkelon and the archaeology of destruction”. Biblical Archaeology Review. 22 (1).

- Stol, Marten (1993). Epilepsy in Babylonia. Brill Publishers.

- Louvre Museum

- Vatican Museums

- British Museum

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Rijksmuseum

- Ashmolean Museum

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Field Museum of Natural History