The Story of Writing

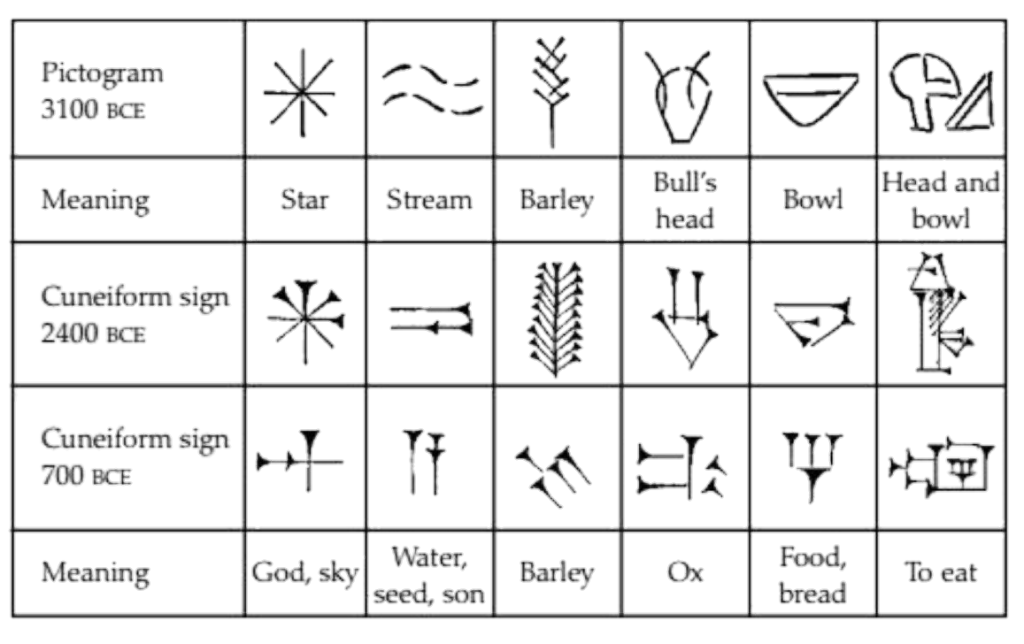

PEPOLE WHO LIVED as hunters and nomads did not need written records. As the first cities arose, people began to require records of ownership, business deals, and government. The Sumerians devised the world’s first script or writing system. At first they used picture symbols to represent objects such as cattle, grain, or fish. By around 3300 BCE the citizens of Uruk were using about 700 different symbols, or pictographs. These were pressed into soft clay with a stylus, leaving a wedge-shaped mark that then hardened. Over the centuries the marks developed into a script that represented sound as well as meaning. Archaeologists call this cuneiform(wedge-shaped) writing. It was used by later Mesopotamian people including the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians.

In a world in which immediate access to words and information is taken for granted, it is hard to imagine a time when writing began.

Archaeological discoveries in ancient Mesopotamia (now mostly modern Iraq) show the initial power and purpose of writing, from administrative and legal functions to poetry and literature.

Mesopotamia was a region comprising many cultures over time speaking different languages. The earliest known writing was invented there around 3400 B.C. in an area called Sumer near the Arabian Gulf. The development of a Sumerian script was influenced by local materials: clay for tablets and reeds for styluses (writing tools). At a little later, the Egyptians were inventing their own form of hieroglyphic writing.

Even after Sumerian died out as a spoken language around 2000 B.C., it survived as a scholarly language and script. Other peoples within and near Mesopotamia, from Turkey, Syria, and Egypt to Iran, adopted the later version of this script developed by the Akkadians (the first recognizable Semitic people), who succeeded the Sumerians as rulers of Mesopotamia. In Babylonia itself, the script survived for two more millennia until its demise around 70 C.E.

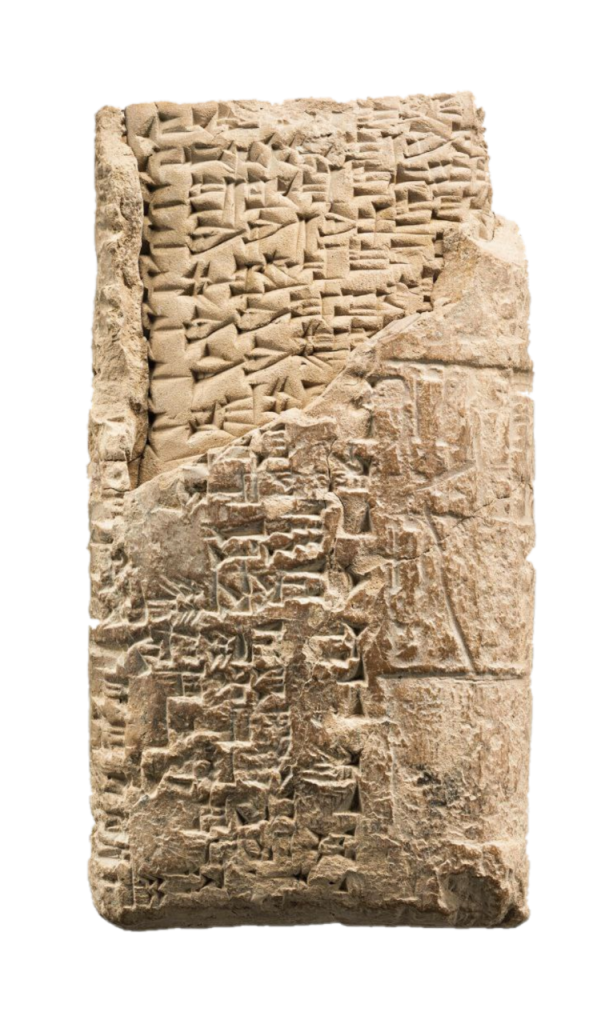

Writing began with pictographs

(picture words) drawn into clay with a pointed tool. This early administrative tablet was used to record food rations for people, shown by a person’s head and bowl visible on the lower left side. Pictographs and numbers show amounts of grain allotted to cities and types of workers, including pig herders and groups associated with a religious festival.

Tablets like these helped local leaders organize, manage, and archive information. This tablet reflects bureaucratic accounting, but similar lists were used in the following centuries by individuals to keep track of personal property and business agreements.

From Pictures to Writing in Everyday Life

Writing evolved when someone decided to replace the pointed drawing tool with a triangular reed stylus. The reed could be pressed easily and quickly into clay to make wedges. At first, the wedges were grouped to make pictures, but slowly the groups evolved into more abstract signs and became the sophisticated script we call cuneiform (“wedge-shaped” in Latin). About one thousand signs represented the names of objects and also stood for words, syllables, and sounds (or parts of them).

Cuneiform records provide information about bureaucracy and authority, but they also document many fascinating aspects of daily life. Written texts reveal how individuals and families expressed their wishes, married and had children, did business, and worshipped. People wrote mainly on clay, but also on more expensive materials such as the golden plaque shown above

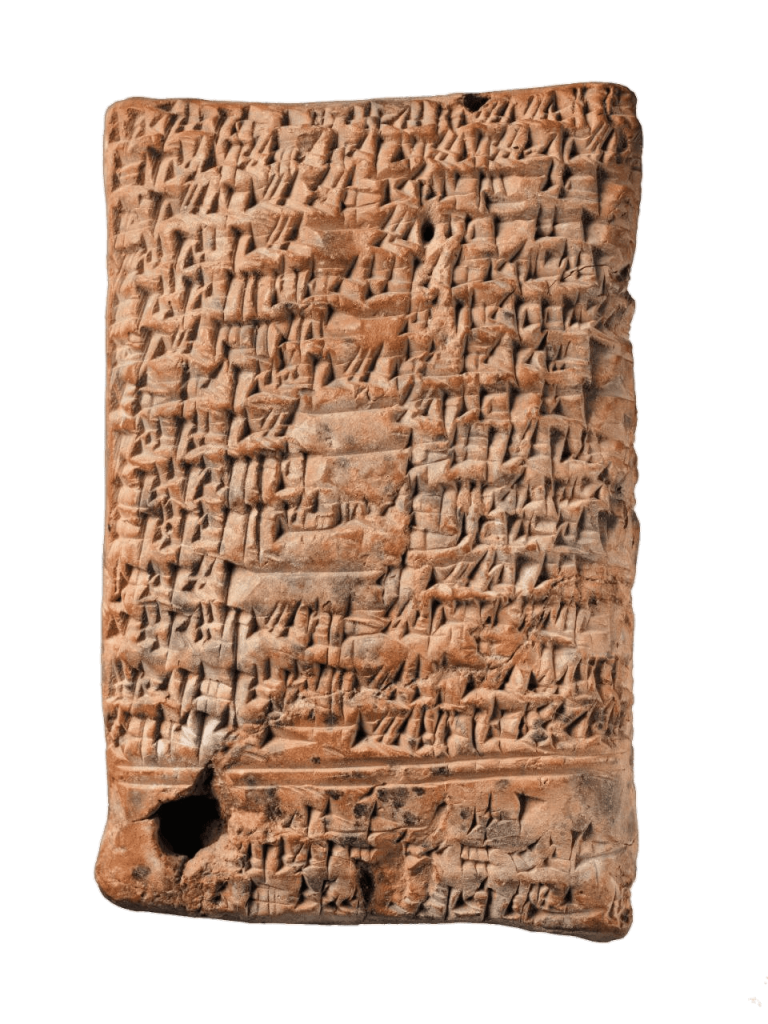

Tablet in Envelope with a Marriage Contract, 1830–1813 B.C., Babylonian Amorite.

In this clay marriage contract, which includes an oath to the chief god of Kish where the marriage would have taken place, a father gives his daughter to her new husband. In turn the husband pays a bride-price of silver to three men, perhaps her brothers. The document is enclosed in a clay envelope. Witnesses each rolled personal seals, inscribed cylinders like small rolling pins, across the left side of the envelope to impress a form of signature in relief

Who Wrote Cuneiform :

Professional writers of cuneiform were called “tablet writers”—scribes. In slow stages of schooling, they learned hundreds of cuneiform signs and memorized texts and templates in different languages. Most were men, but some women could become scribes.

Students’ interests and skills varied, and a proverb noted: A disgraced scribe becomes a man of magical spells. This was a pointed reminder that less-committed students might end up making an uncertain living writing common incantations. Working harder could lead to a prosperous life composing legal document or even writing correspondence for a royal court. Those who persevered could become scholars with knowledge of mathematics, medicine, religious ritual, divination, laws, and mythology, or even authors of literature.

This clay document is one of a series recording scribal training.

This tablet is one of more than 20 similar tablets (nicknamed “Schooldays”) that present the life of a young student in a scribal school. The days were long, filled with copying and memorizing. Older scribes oversaw these efforts, while the school was led by a headmaster. The document records a usual day:

I read my tablet, ate my lunch,

prepared my [new] tablet, wrote it, finished it; then

my model tablets were brought to me;

and in the afternoon, my exercise tablets were brought to me.The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character, 1963, translation by N. Kramer

On this day the boy feels successful, but on the next, his teachers repeatedly beat him for infractions such as tardiness, talking, and poor handwriting. In the end, the boy’s father invites the headmaster to dinner and gives him gifts and money. Appeased (and bought off, although such payments may have been expected), the headmaster declares to the boy: “You have carried out well the school’s activities. You are a man of learning!”

Many people may have learned the basics of reading and writing, including royals. The first known author was Enheduanna, the daughter of Sargon, king of Akkad, the first king to conquer all of Mesopotamia. She was a priestess who composed religious poetry. Later, the Neo-Assyrian king Ashurbanipal praised his own literacy and scholarship. He is sometimes shown in royal art with a writing stylus stuck in his belt.

Although cuneiform endured for over three thousand years, as simpler alphabets became common the script was eventually used only for scholarly documents, and it faded away completely in the late-first century A.D. Within a few centuries, all understanding of the once-dominant writing was lost for about 1,800 years

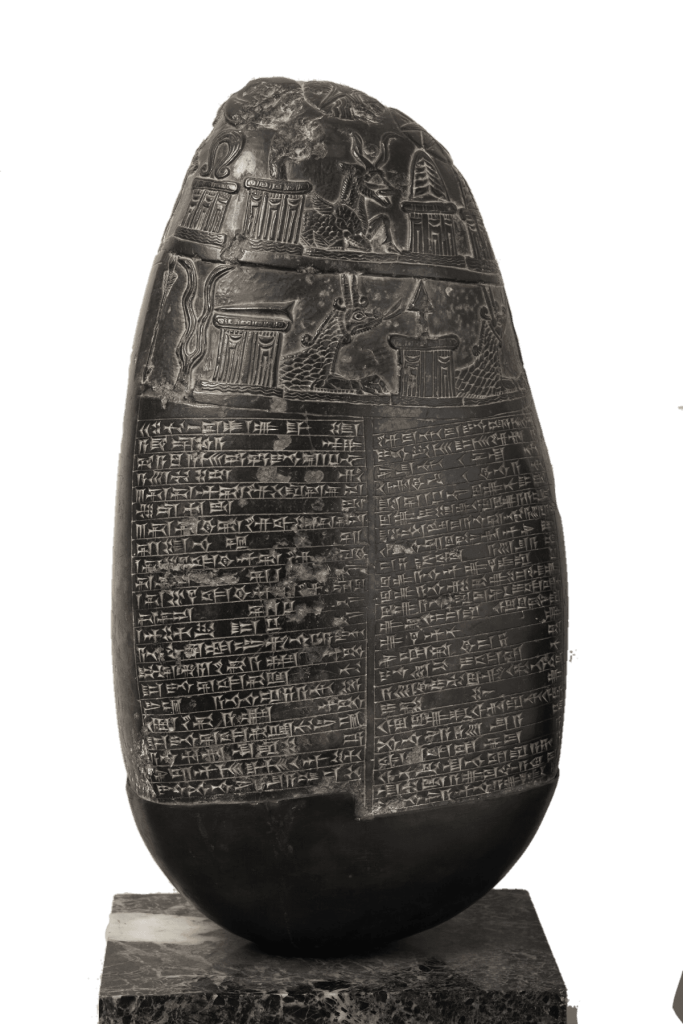

Border Stone black kudurru

In the 1700s, scholars began to take note of cuneiform on surviving clay fragments and stone monuments, but they did not understand what was written. In 1786, when a French traveler brought this dramatic black kudurru, a small stone monument, to Paris, inventive translations of the text were proposed, such as “The army of heaven gives us vinegar to drink solely to provide us remedies able to bring us healing.”

When its true meaning was eventually deciphered, the stone was found to record a gift of land from a father to his daughter upon her marriage. The careful father stipulates that her new father-in-law will not claim the land as his. The horned, scaly being at the top of the stone is Nabu, a divine patron of scribes who oversees the proper execution of the contract.

The text was written in Akkadian cuneiform, the written language of the Sumerians, which was undeciphered until the mid-1800s

By then, some scholars were convinced that they could read Akkadian texts. Others thought they were just guessing. Finally, in 1857 the Royal Asiatic Society issued a challenge to four experts: Provide independent translations of a newly found, unpublished Akkadian inscription for judgment by a jury. Each academic received a copy of the inscription and returned a translation within a set time.

The text was an account of a king’s military successes. One dramatic excerpt declared: “Their carcasses covered the valleys and the tops of the mountains. I cut off their heads. The battlements of their cities I made heaps of, like mounds of earth!” The scholars were vindicated when a jury found their translations similar and declared Akkadian cuneiform deciphered! Read the account here.

In the 1800s and 1900s, archaeological excavations revealed thousands of cuneiform documents, and the variations of the script across languages and time were slowly deciphered.

While we can read cuneiform documents today, the majority—many hundreds of thousands—still survive unread, and the few hundred cuneiform experts worldwide face an impossible task. Fortunately, machine learning offers potential assistance. Scholars at many institutions are compiling databases and training machines to read and fill in gaps in these ancient texts

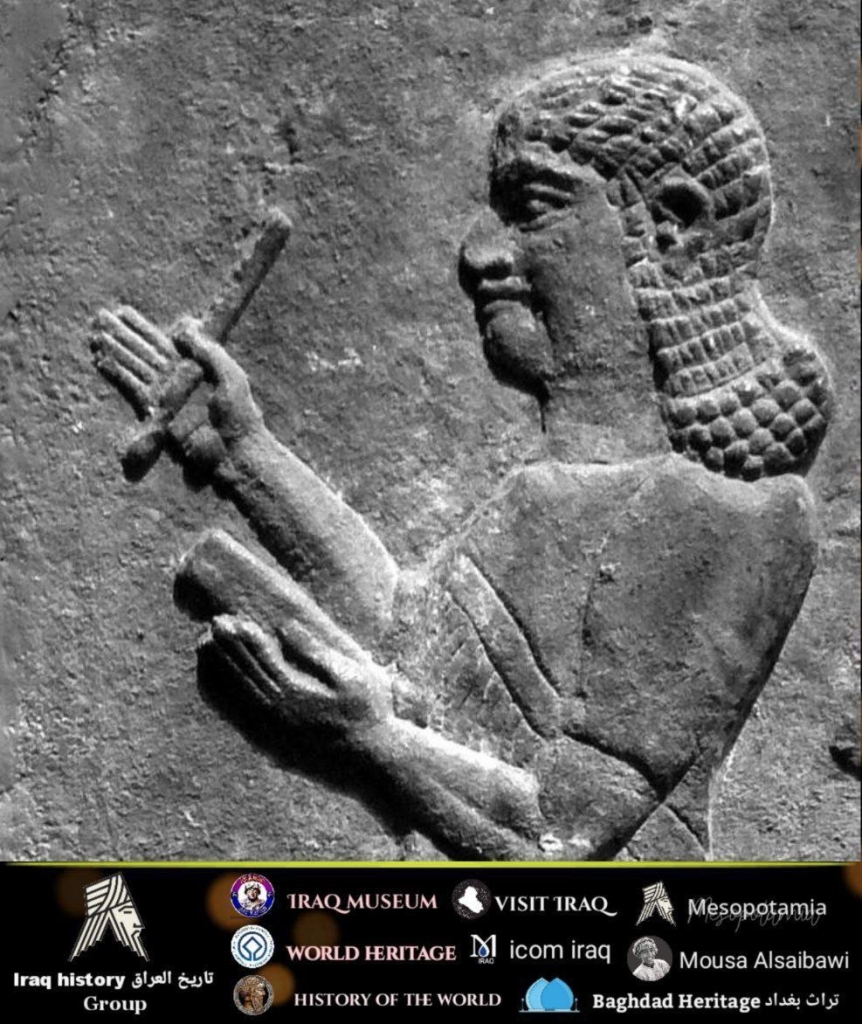

Writer of cuneiform tablets

decoration of Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser III’s Central Palace at Kalhu Iraq modern Nimrud photo by Greta Van Buylaere

Our Sources :

History Begins at Sumer (Philadelphia, 1956), Thirty Nine Firsts in Recorded History, by Samuel Noah Kramer, in 404 searchable pdf pages.

Selected Writings of Samuel Noah Kramer, in 570 bookmarked and searchable pdf pages.

Green، M.W. (1981). “The Construction and Implementation of the Cuneiform Writing System

Samuel Noah Kramer University of Pennsylvania Press, 1972 – History – 130 pages

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1944). Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C. American Philosophical Society. Revised edition: 1961.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1981). History Begins at Sumer: Thirty-Nine Firsts in Man’s Recorded History (3 ed.). University of Pennsylvania Press. I. First edition: 1956 (Twenty-Five Firsts). Second Edition: 1959 (Twenty-Seven Firsts).

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1963). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character Samuel Noah Kramer (PDF). University of Chicago Press.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1967). Cradle of Civilization: Picture-text survey that reconstructs the history, politics, religion and cultural achievements of ancient Sumer, Babylonia and Assyria. Time-Life: Great Ages of Man: A History of the World’s Cultures..

- Wolkstein, Diane; Kramer, Samuel Noah (1983). Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-090854-8.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1988a). In the World of Sumer: An Autobiography. Wayne State University Press

- Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization. Paul Kriwaczek.

Ancient Mesopotamia. Leo Oppenheim.

Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History. University of Chicago.

Mesopotamia 8000-2000 B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

30,000 Years of Art. Editors at Phaidon. - Treasures of the Iraq Museum Faraj Basmachi Ministry of Information, 1976 – Art, Iraqi – 426 pages

- Algaze, Guillermo, 2008 Ancient Mesopotamia at the Dawn of Civilization: the Evolution of an Urban Landscape. University of Chicago Press

- Atlas de la Mésopotamie et du Proche-Orient ancien, Brepols, 1996

- Bottéro, Jean; 1987. (in French) Mésopotamie. L’écriture, la raison et les dieux, Gallimard, coll. « Folio Histoire »,

- Bottéro, Jean (15 June 1995). Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods. Translated by Bahrani, Zainab; Van de Mieroop, Marc. University of Chicago Press.

- Edzard, Dietz Otto; 2004. Geschichte Mesopotamiens. Von den Sumerern bis zu Alexander dem Großen, München,

- Hrouda, Barthel and Rene Pfeilschifter; 2005. Mesopotamien. Die antiken Kulturen zwischen Euphrat und Tigris. München 2005 (4. Aufl.),

- Joannès, Francis; 2001. Dictionnaire de la civilisation mésopotamienne, Robert Laffont.

- Korn, Wolfgang; 2004. Mesopotamien – Wiege der Zivilisation. 6000 Jahre Hochkulturen an Euphrat und Tigris, Stuttgart,

- Matthews, Roger; 2005. The early prehistory of Mesopotamia – 500,000 to 4,500 BC, Turnhout 2005,

- Oppenheim, A. Leo; 1964. Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a dead civilization. The University of Chicago Press: Chicago and London. Revised edition completed by Erica Reiner, 1977.

- Pollock, Susan; 1999. Ancient Mesopotamia: the Eden that never was. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- Postgate, J. Nicholas; 1992. Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the dawn of history. Routledge: London and New York.

- Roux, Georges; 1964. Ancient Iraq, Penguin Books.

- Silver, Morris; 2007. Redistribution and Markets in the Economy of Ancient Mesopotamia: Updating Polanyi, Antiguo Oriente

- Pingree, David (1998). “Legacies in Astronomy and Celestial Omens”. In Dalley, Stephanie (ed.). The Legacy of Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press.

- Stager, L. E. (1996). “The fury of Babylon: Ashkelon and the archaeology of destruction”. Biblical Archaeology Review. 22 (1).

- Stol, Marten (1993). Epilepsy in Babylonia. Brill Publishers.

- Gelb, I. et al. (1956-2010) Chicago Assyrian Dictionary (The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental

- Institute of the University of Chicago). 26 vols., Chicago.

- Huehnergard, J. (2005) A Grammar of Akkadian. Winona Lake. Sasson, J.-M. (2015) From the Mari Archives. An Anthology of Old Babylonian Letters. Winona

- Louvre Museum

- Vatican Museums

- British Museum

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Rijksmuseum

- Ashmolean Museum

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Field Museum of Natural History