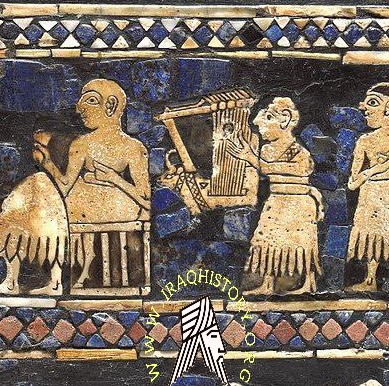

The nearly half million cuneiform tablets excavated from ancient Near Eastern sites provide us with ample evidence for the uses of music in ancient Sumer, Akkad , Babylonia, and Assyria, hatra , Abbasid period Pictorial representations of musical instruments, singers, religious and magic rituals, dancers, acrobats, and sporting events likewise testify to the importance of music in these ancient societies And, the discovery of the physical remains of musical instruments at the site of Ur has added a further dimension to our knowledge. Were it not for the eleven stringed instruments recovered at Ur (two harps and nine lyres), we would not have a single actual stringed instrument from ancient Sumer-Babylonia. The Ur graves also yielded a pair of silver wind instruments and a small number of other types of instruments; a few other prehistoric Mesopotamian sites have given us fragments of bone wind instruments

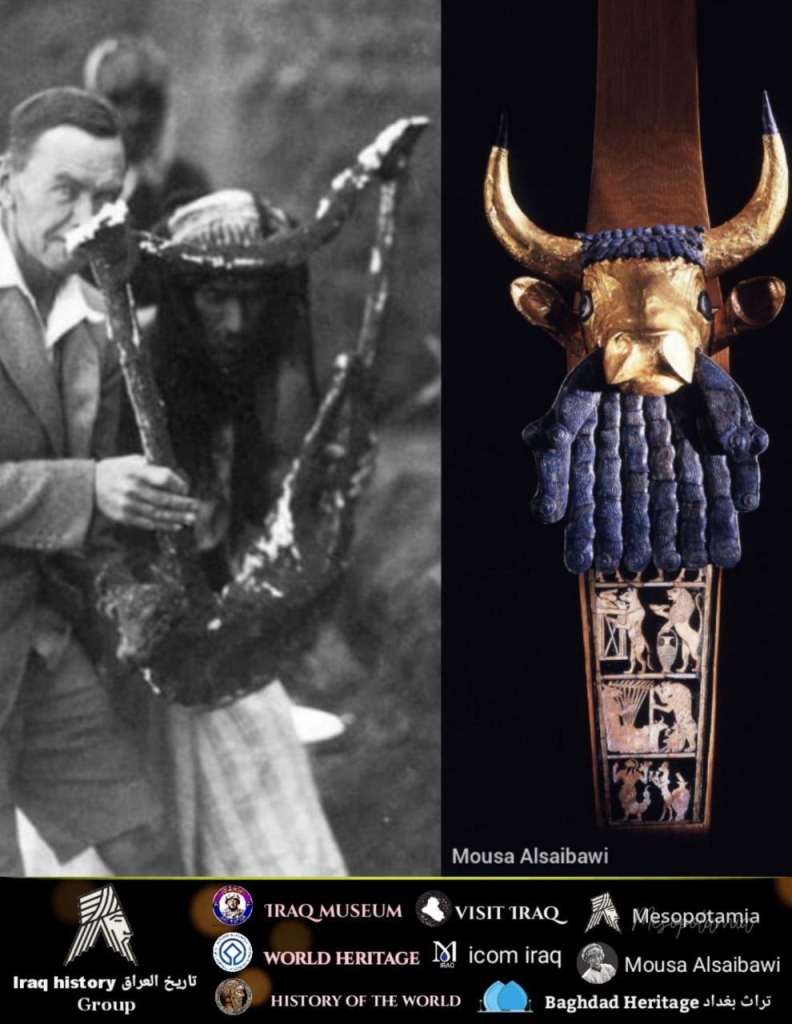

This is an extremely early stringed instrument perhaps the earliest in the world. It comes from one of the earliest human civilisations Sumer in Mesopotamia iraq excavated in Royal Cemetery of Ur They date back to the Early Dynastic III Period of Sumerian civilization Mesopotamia iraq between about 2600 BC in 1928 archaeologists led by the British archaeologist Leonard Woolley representing a joint expedition of the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania

Detail from the panel on the Bull-Headed Lyre showing an 8-stringed bovine lyre being played. At the top of the lyre, braided material is wrapped around the crossbar under the tuning sticks. The small fox-like animal facing the front of the lyre holds a sistrum or rattle

Scales and Tuning in Ancient Music

Among the many cuneiform tablets studied we have been fortunate to have recognized, since 1959, a small number of texts that relate to the tuning and playing of ancient instruments Thus far, cuneiformists have identified ten Mesopotamian tablets that contain technical information about ancient musical scales. We now know that by the Old Babylonian period in ancient Iraq (i.e., by at least ca. 1800 BC, or about 850 years after the period of the Royal Cemetery of Ur), there existed standardized tuning procedures that operated within a heptatonic, diatonic system consisting of seven different and interrelated scales (see box with Glossary of Musical Terms). The fact that these seven scales could be equated with seven ancient Greek scales (dating some 1400 years later) quite startled the scholarly community; and the fact that one of the scales in common use was equivalent to our own modern major scale (do-re-mi. . . ) seemed difficult for many to believe (Fig. 6). But research on the part of several cuneiformists and musicologists working together has been strengthened over the years by the steady accumulation of cuneiform tablets that use the same standard corpus of Akkadian terms to designate the names of the musical strings; the names of the instruments and their parts; fingering techniques; the names of musical intervals (fifths, fourths, thirds, and sixths); and the names of the seven scales that derive their nomenclature from the particular interval of a fourth or a fifth on which the tuning procedure starts.

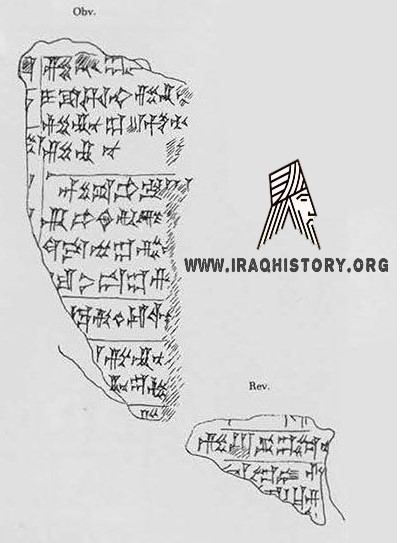

Hand copy of a fragmentary cuneiform tablet from Nippur. The text concerns Old Babylonian instructions related to the playing and singing of hymn

Two of these important technical texts came from the site of Ur, while three others came from another rich Sumerian site, the ancient city of Nippur. It is highly probable that the tuning systems evidenced in the Akkadian language in texts dating from the Old Babylonian to the Neo-Babylonian period (ca. 1800-500 BO had earlier Sumerian antecedents, because many of the technical terms in Akkadian have Sumerian equivalents.

We also know that the Sumero-Babylonian musical system was exported at least as far away as the Mediterranean coast, for the same Akkadian corpus of terms was used for instructions to instrumentalists performing Hurrian cult hymns in ancient Ugarit (modern Ras Sham) in Syria. It is not a stretch of the imagination to suggest that the ancient Greeks did, as Pythagoras said, learn Mesopotamian music theory—together with their mathematics—in the Near East.

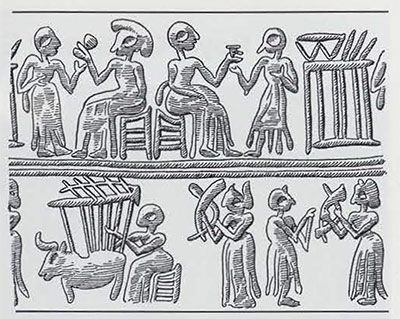

Scene on a gold cylinder seal from a grave in the Ur cemetery In the bottom register are cymbalists” (figures palying clappers), a dancer, and a seated figure playing a bovine lyre. The top register shows festive banqueters

Ur excavations Iraq mesopotamia (1900)

Joint Expedition of the British Museum and of the Museum of the University of Pennsylvania to Mesopotamia

Our Sources : University of Pennsylvania

History Begins at Sumer (Philadelphia, 1956), Thirty Nine Firsts in Recorded History, by Samuel Noah Kramer, in 404 searchable pdf pages.

Selected Writings of Samuel Noah Kramer, in 570 bookmarked and searchable pdf pages.

Green، M.W. (1981). “The Construction and Implementation of the Cuneiform Writing System

Samuel Noah Kramer University of Pennsylvania Press, 1972 – History – 130 pages

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1944). Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C. American Philosophical Society. Revised edition: 1961.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1981). History Begins at Sumer: Thirty-Nine Firsts in Man’s Recorded History (3 ed.). University of Pennsylvania Press. I. First edition: 1956 (Twenty-Five Firsts). Second Edition: 1959 (Twenty-Seven Firsts).

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1963). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character Samuel Noah Kramer (PDF). University of Chicago Press.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1967). Cradle of Civilization: Picture-text survey that reconstructs the history, politics, religion and cultural achievements of ancient Sumer, Babylonia and Assyria. Time-Life: Great Ages of Man: A History of the World’s Cultures..

- Wolkstein, Diane; Kramer, Samuel Noah (1983). Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer. New York: Harper & Row.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1988a). In the World of Sumer: An Autobiography. Wayne State University Press

- Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization. Paul Kriwaczek.

Ancient Mesopotamia. Leo Oppenheim.

Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History. University of Chicago.

Mesopotamia 8000-2000 B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

30,000 Years of Art. Editors at Phaidon. - Treasures of the Iraq Museum Faraj Basmachi Ministry of Information, 1976 – Art, Iraqi – 426 pages

- Algaze, Guillermo, 2008 Ancient Mesopotamia at the Dawn of Civilization: the Evolution of an Urban Landscape. University of Chicago Press

- Atlas de la Mésopotamie et du Proche-Orient ancien, Brepols, 1996

- Bottéro, Jean; 1987. (in French) Mésopotamie. L’écriture, la raison et les dieux, Gallimard, coll. « Folio Histoire »,

- Edzard, Dietz Otto; 2004. Geschichte Mesopotamiens. Von den Sumerern bis zu Alexander dem Großen, München,

- Hrouda, Barthel and Rene Pfeilschifter; 2005. Mesopotamien. Die antiken Kulturen zwischen Euphrat und Tigris. München 2005 (4. Aufl.),

- Joannès, Francis; 2001. Dictionnaire de la civilisation mésopotamienne, Robert Laffont.

- Korn, Wolfgang; 2004. Mesopotamien – Wiege der Zivilisation. 6000 Jahre Hochkulturen an Euphrat und Tigris, Stuttgart,

- Matthews, Roger; 2005. The early prehistory of Mesopotamia – 500,000 to 4,500 BC, Turnhout 2005,

- Oppenheim, A. Leo; 1964. Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a dead civilization. The University of Chicago Press: Chicago and London. Revised edition completed by Erica Reiner, 1977.

- Pollock, Susan; 1999. Ancient Mesopotamia: the Eden that never was. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- Postgate, J. Nicholas; 1992. Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the dawn of history. Routledge: London and New York.

- Roux, Georges; 1964. Ancient Iraq, Penguin Books.

- Silver, Morris; 2007. Redistribution and Markets in the Economy of Ancient Mesopotamia: Updating Polanyi, Antiguo Oriente

- Pingree, David (1998). “Legacies in Astronomy and Celestial Omens”. In Dalley, Stephanie (ed.). The Legacy of Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press.

- Stager, L. E. (1996). “The fury of Babylon: Ashkelon and the archaeology of destruction”. Biblical Archaeology Review. 22 (1).

- Stol, Marten (1993). Epilepsy in Babylonia. Brill Publishers.

- Louvre Museum

- Vatican Museums

- British Museum

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Rijksmuseum

- Ashmolean Museum

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Field Museum of Natural History