Mesopotamian Mathematics

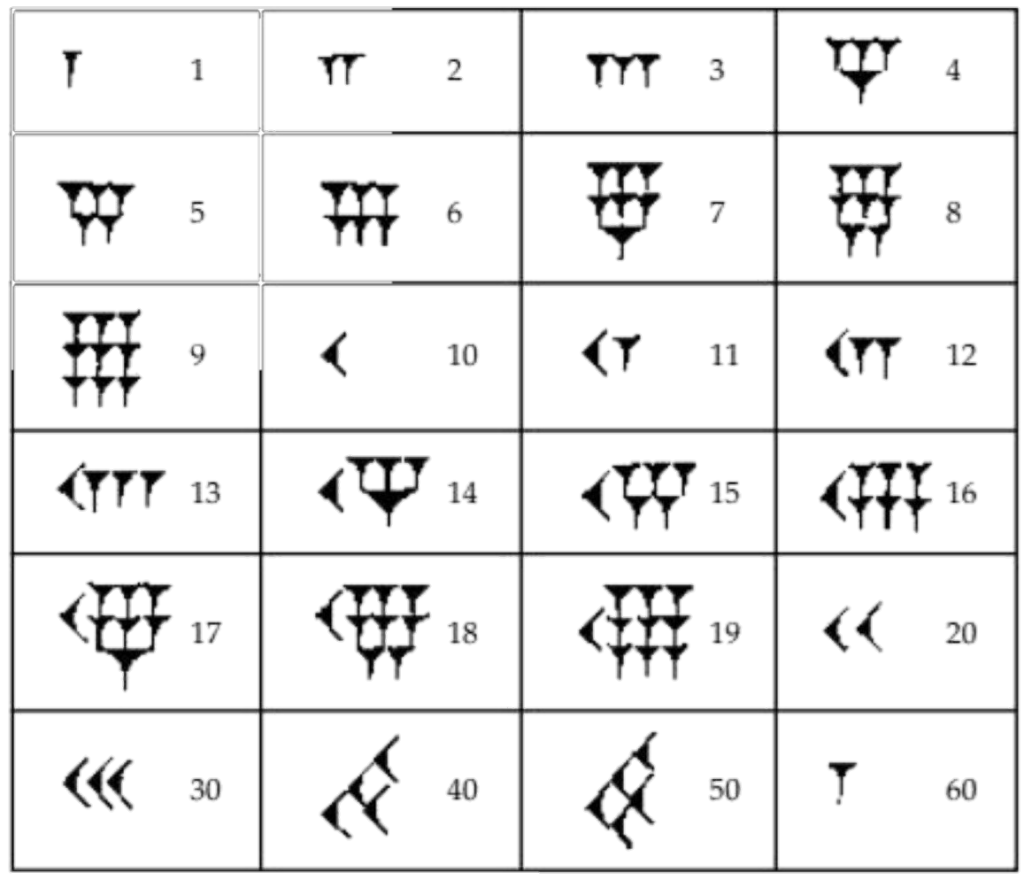

rimitive people counted using simple methods, such as putting notches on bones, but it was the Sumerians who developed a formal numbering system based on units of 60, according to Robert E. and Carolyn Krebs’ book, Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the Ancient World. At first, they used reeds to keep track of the units, but eventually, with the development of cuneiform, they used vertical marks on the clay tablets. Their system helped lay the groundwork for the mathematical calculations

The purpose of this page is to provide a source of information on all aspects of Mesopotamian mathematics. We explain the origins of mathematics in Mesopotamia from the earliest tokens, through the development of Sumerian mathematics to the grand flowering in the Old Babylonian civilization, and on into the later civilization of Mesopotamian history.

Sumerian metrological numeration systems

By about 3000 BC, the Sumerians were drawing images of tokens on clay tablets. At this point, different types of goods were represented by different symbols, and multiple quantities represented by repetition. Three units of grain were denoted by three ‘grain-marks’, five jars of oil were denoted by five ‘oil-marks’ and so on

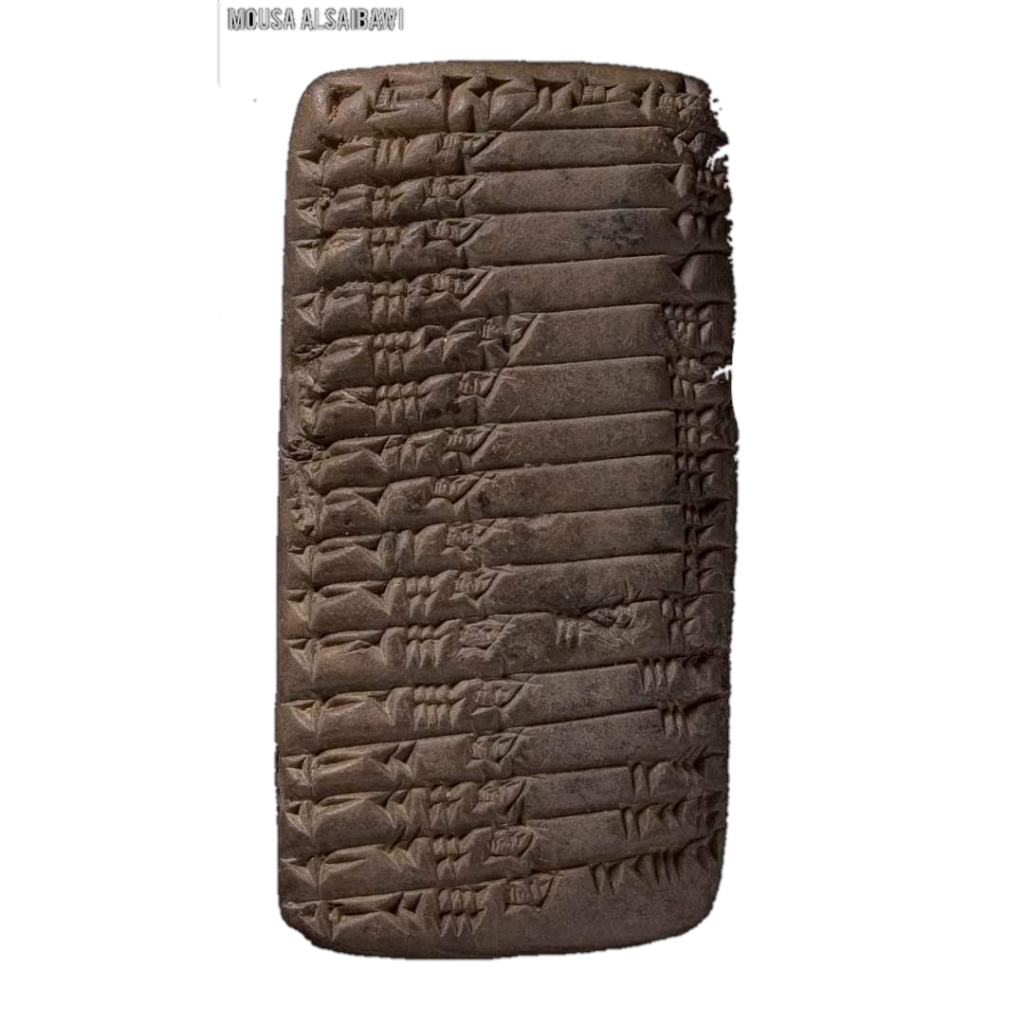

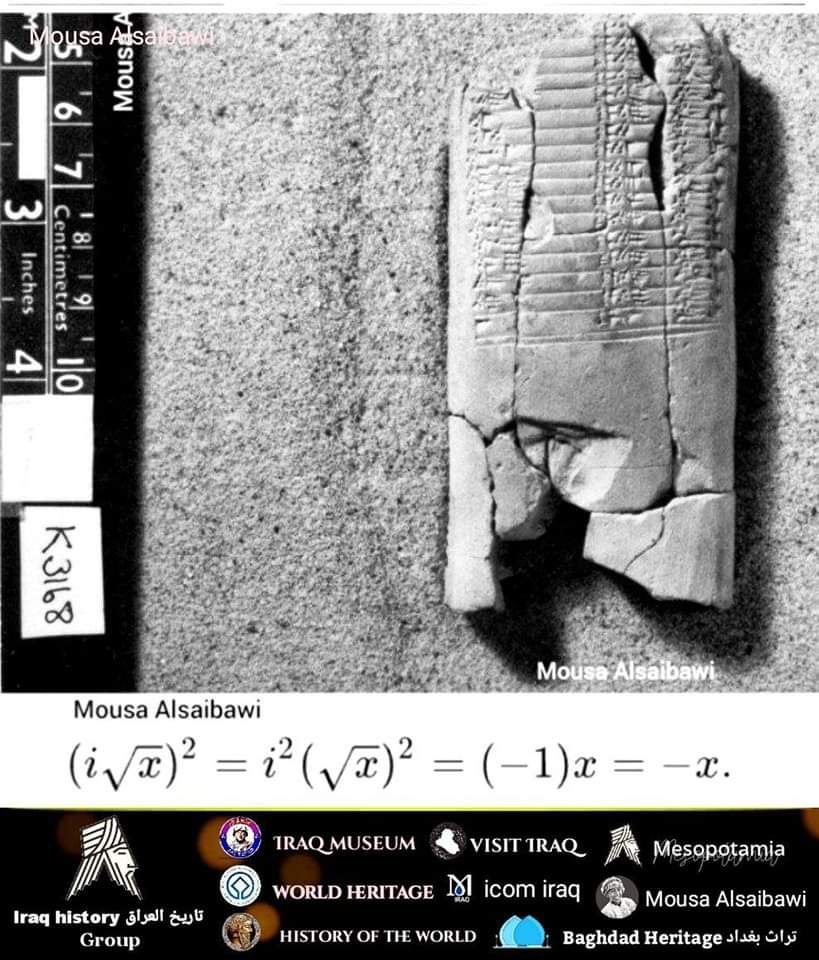

a school exercise text – a table of reciprocals of the number 60

2112 BC – c. 2004 BC Mesopotamia iraq Sumerian civilization

Mathematical cuneiform

documents from various sites and periods provide a wealth of information about the conceptualization and practice of mathematics in ancient Mesopotamia. The corpus is especially rich for the Old Babylonian period (ca. 1900 – 1600 BCE), and from these documents we can observe a systematic approach to the transmission of mathematical knowledge and tools.

The most common evidence for mathematical knowledge in ancient Mesopotamia is given by cuneiform tablets that were used in the teaching and learning process, either in a school itself, or, as might be the case of the so-called advanced mathematics, some erudite environment connected to the schools. Another category of evidence is given by cuneiform documents that integrated professional practice: the planning of a canal, loan contracts, inventories, and land-division diagrams are documents whose effectiveness depended on skills in counting, measuring, calculating, and doing geometry. Indirect evidence also comes from material culture that reflects the application of mathematical calculations, such as buildings, irrigation networks, the fabrication of bricks, the division of work, and the distribution of food rations. To all this, we could add what became known as “eduba texts”: narratives which portray the life within the schools in Mesopotamia, especially in the Old Babylonian period, giving an important place to mathematics.

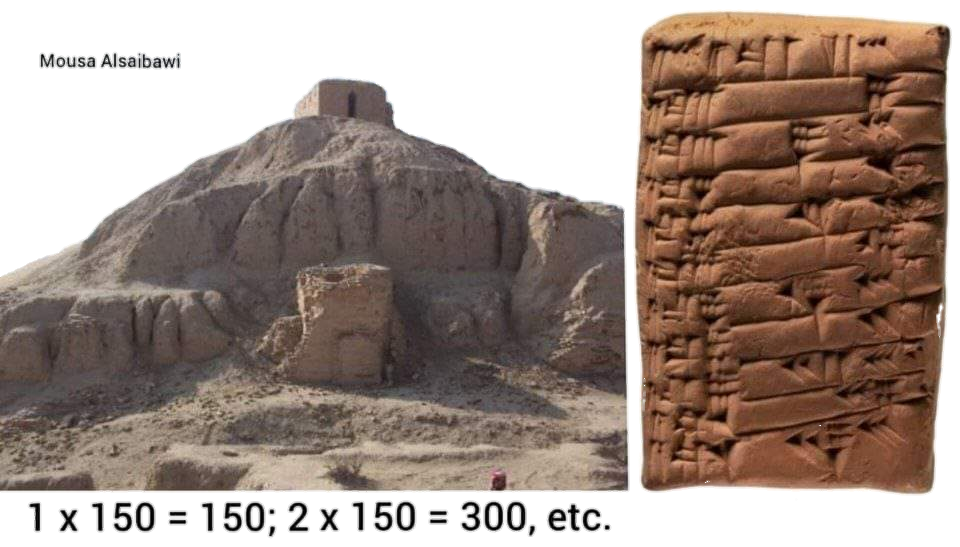

Baked clay tablet Temple library

Multiplication Tablet: 1 x 150 = 150 2 x 150 = 300 etc

Iraq Nippur mesopotamia

Archaeology Area : Temple Hill

Period : Old Babylonian Period

Date Made 1900 – 1600 BCE

Mathematical table

It contains contains a table of reciprocal numbers followed by 37 different multiplication tables, with 12 or the original 13 columns still preserved.

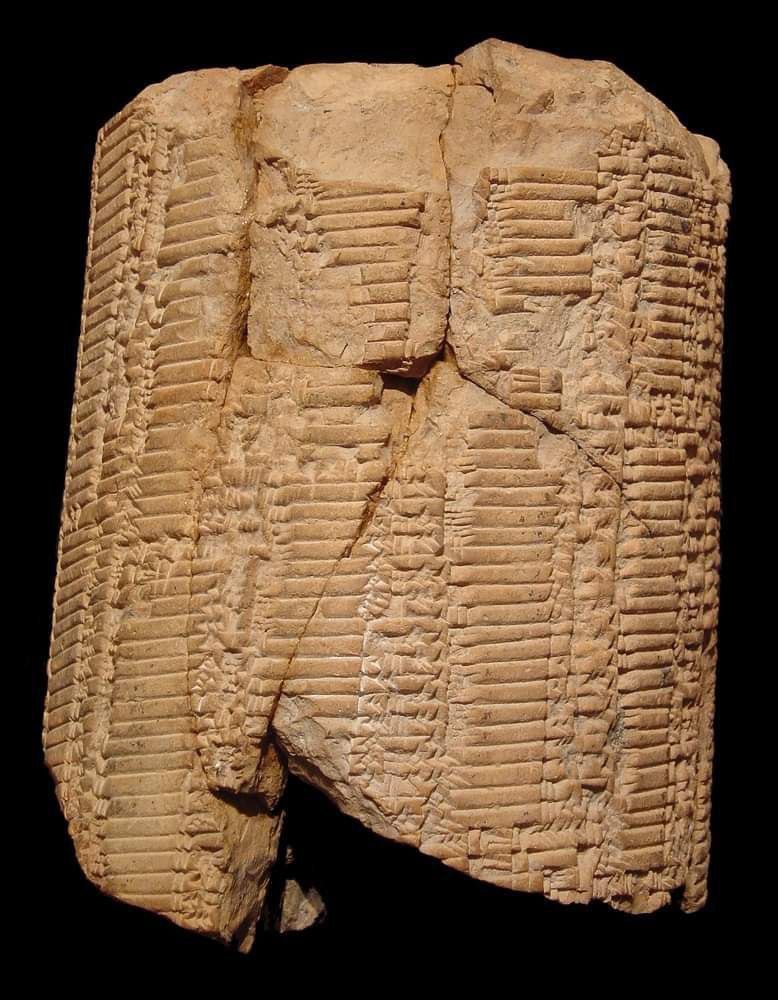

Iraq Mesopotamia, Diyala region Old Babylonian period (ca. 2000-1600 BCE)

Clay tablet

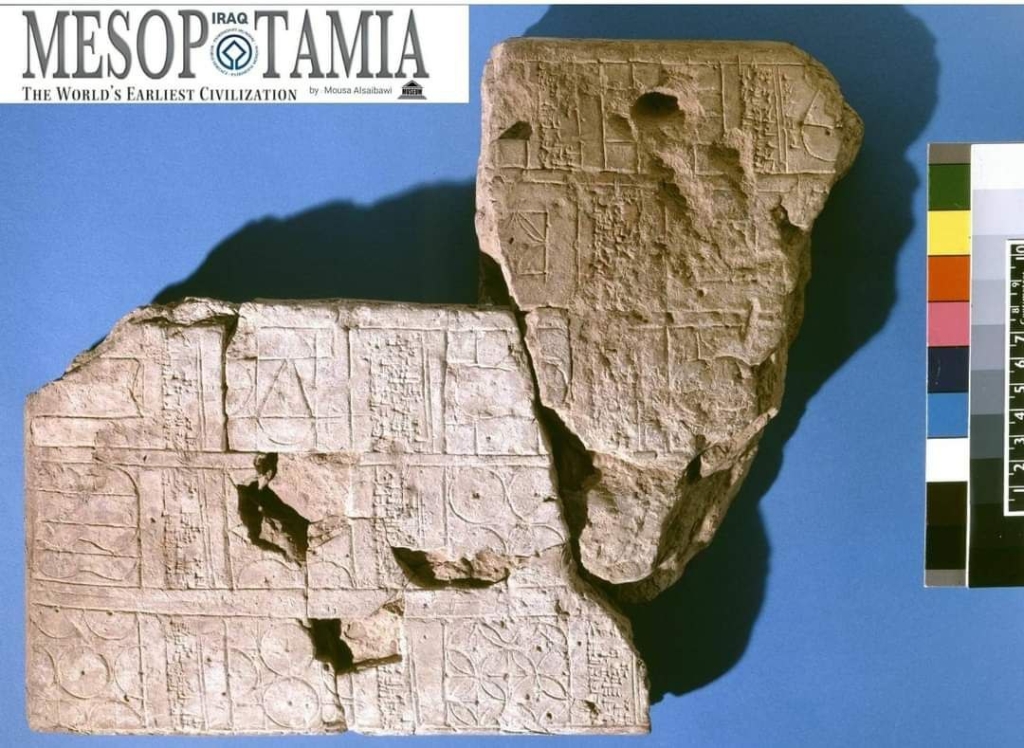

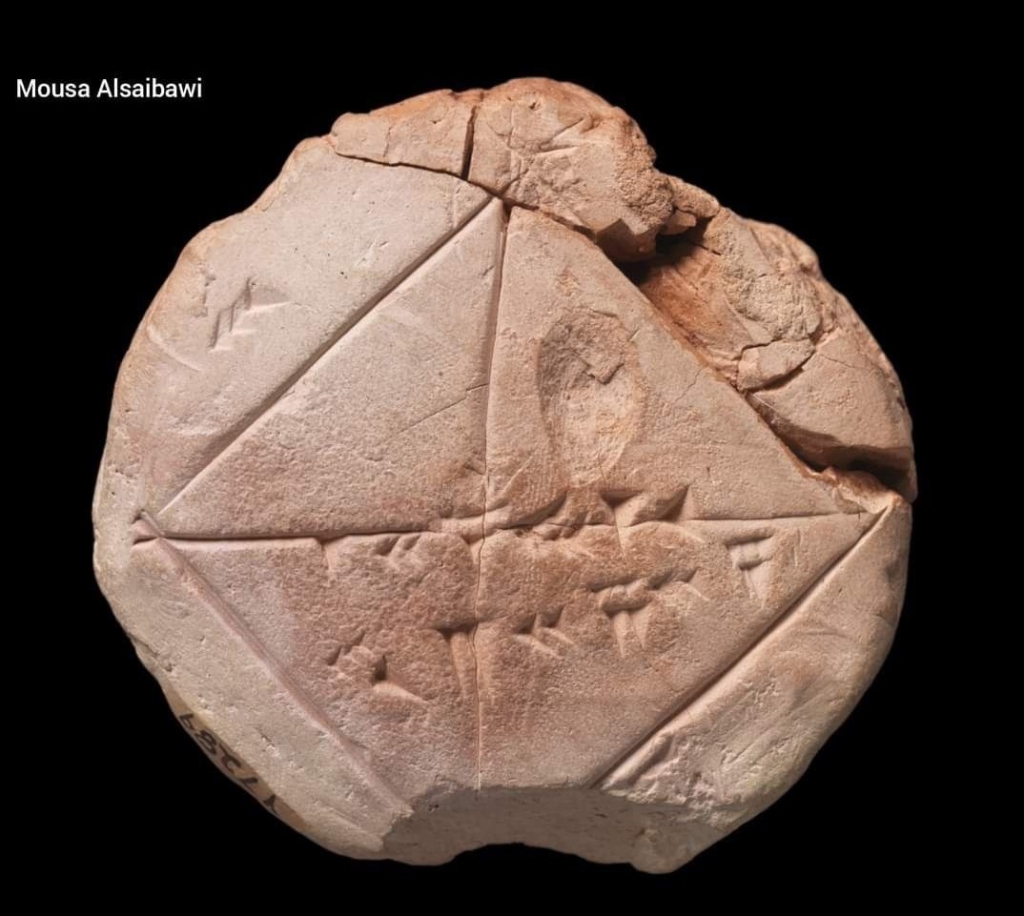

geometrical diagrams accompanied by problems Old Babylonian Mesopotamia iraq

mathematical table of square roots

Fragment of a clay tablet, a , 27 + 17 lines of inscription, Old Babylonian civilization mesopotamia Iraq

Excavated by: Sir Austen Henry Layard Findspot: Larsa Iraq

Mathematical school

of its highlights are a mathematical school tablet which approximates the square root of 2, which belongs to a large corpus of mathematical texts in the collection. Among the literature housed

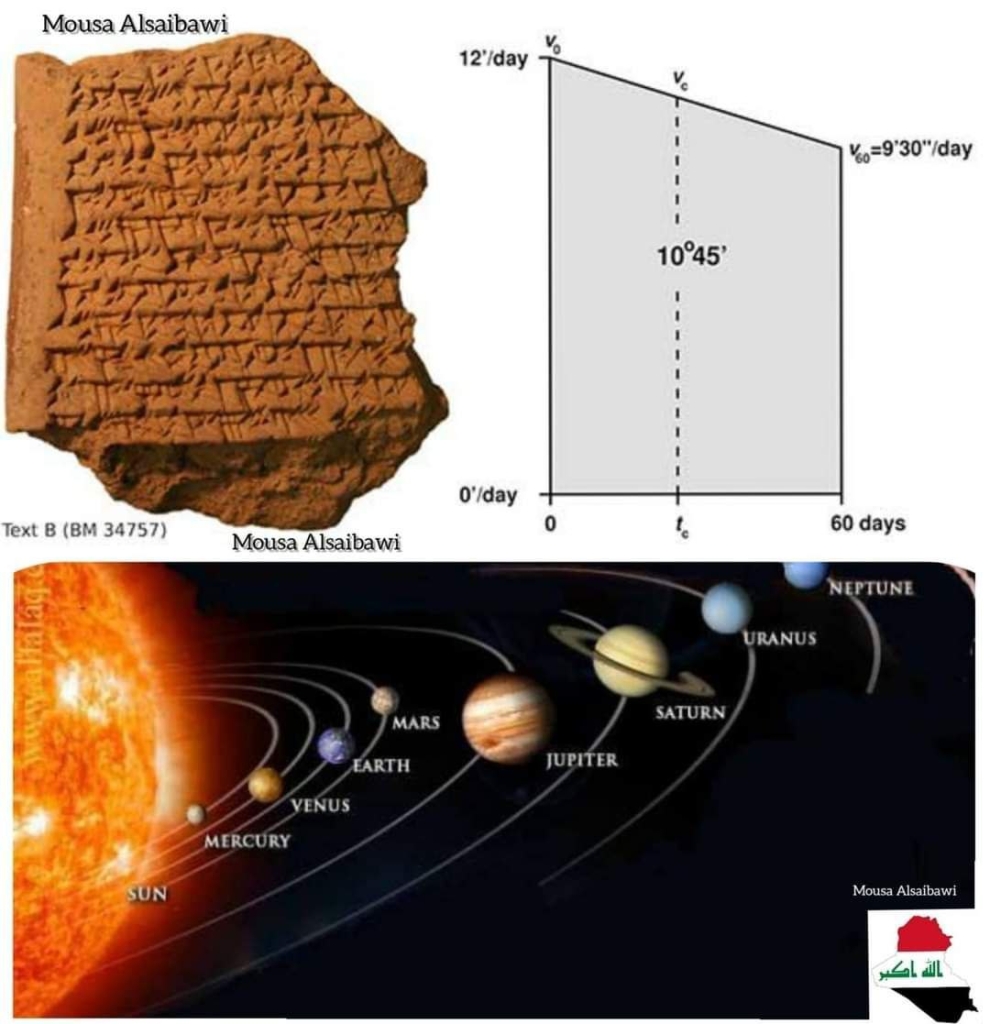

Babylonian astronomical tablet

At right this diagram shows how the distance traveled by Jupiter after 60 days 10º45 is calculated as the area of the trapezoid The Babylonians knew they could then divide this trapezoid into two smaller ones of equal area in order to find the time in which Jupiter covers half the distance it travels in 60 days Mesopotamia iraq

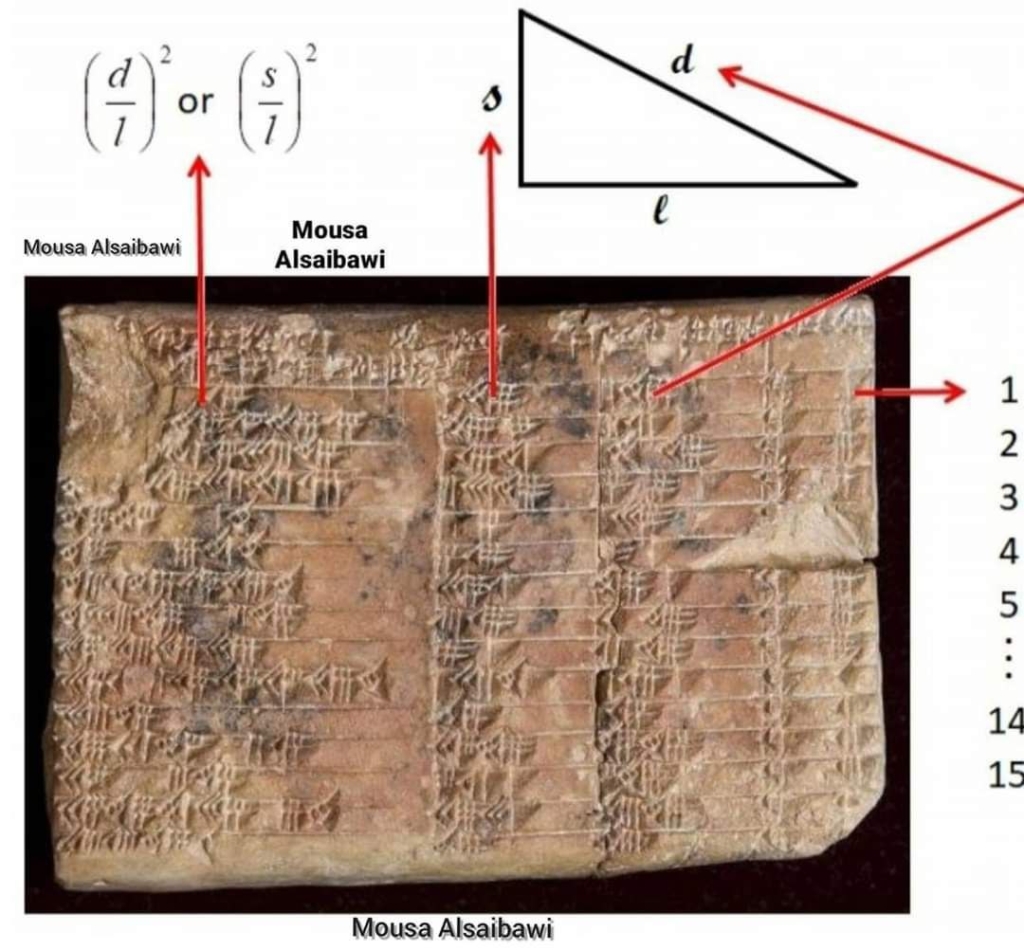

Plimpton 322

world’s oldest and most accurate trigonometric table

A 3700-year-old Babylonian clay tablet discovered in Mesopotamia iraq

rewrites the history of Mathematics mystery was cracked by researchers, revealing it is the world’s oldest and most accurate trigonometric table possibly used by ancient mathematical scribes to calculate how to construct palaces and temples and build canals. The new research shows that Babylonians, not Greeks, were the first to study trigonometry and reveals an ancient mathematical sophistication that had been hidden until now There is substantial evidence that the Babylonians were aware of the Pythagorean theorem even though they may not have had anything similar to a proof

Old Babylonian Weights and Measures

The metrology of ancient Mesopotamia is very complicated, but key to understanding much of the mathematics as units are often silently converted in the middle of a problem. Units of length, weight, area, capacity and so on and the relationships between them changed frequently in both space and time. However, by the Old Babylonian period, the systems were much simpler than during the Sumerian period. For the large bulk of mathematical problem texts, there is a relatively standardized set of measurements, although there are plenty of exceptions. The tables below give the main units in this standard set, but are by no means comprehensive. For up-to-date and detailed references on the different systems, see the articles by Marvin Powell in RLA and Civilizations of the Ancient Near East.

Even in the Old Babylonian times, metrology had a rich collection of units. Most of the conversion factors are simple fractions or multiples of the base 60

Duck Weights Babylonian cavillation

The Mesopotamians used sets of standard weights in conducting business and set stiff penalities for those who used false weights. The weights themselves were usually made of a very hard stone like hematite.

Our Sources :

History Begins at Sumer (Philadelphia, 1956), Thirty Nine Firsts in Recorded History, by Samuel Noah Kramer, in 404 searchable pdf pages.

Selected Writings of Samuel Noah Kramer, in 570 bookmarked and searchable pdf pages.

Green، M.W. (1981). “The Construction and Implementation of the Cuneiform Writing System

Samuel Noah Kramer University of Pennsylvania Press, 1972 – History – 130 pages

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1944). Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C. American Philosophical Society. Revised edition: 1961.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1981). History Begins at Sumer: Thirty-Nine Firsts in Man’s Recorded History (3 ed.). University of Pennsylvania Press. I. First edition: 1956 (Twenty-Five Firsts). Second Edition: 1959 (Twenty-Seven Firsts).

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1963). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character Samuel Noah Kramer (PDF). University of Chicago Press.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1967). Cradle of Civilization: Picture-text survey that reconstructs the history, politics, religion and cultural achievements of ancient Sumer, Babylonia and Assyria. Time-Life: Great Ages of Man: A History of the World’s Cultures..

- Wolkstein, Diane; Kramer, Samuel Noah (1983). Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer. New York: Harper & Row

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1988a). In the World of Sumer: An Autobiography. Wayne State University Press

- Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization. Paul Kriwaczek.

Ancient Mesopotamia. Leo Oppenheim.

Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History. University of Chicago.

Mesopotamia 8000-2000 B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

30,000 Years of Art. Editors at Phaidon. - Treasures of the Iraq Museum Faraj Basmachi Ministry of Information, 1976 – Art, Iraqi – 426 pages

- Algaze, Guillermo, 2008 Ancient Mesopotamia at the Dawn of Civilization: the Evolution of an Urban Landscape. University of Chicago Press

- Atlas de la Mésopotamie et du Proche-Orient ancien, Brepols, 1996

- Bottéro, Jean; 1987. (in French) Mésopotamie. L’écriture, la raison et les dieux, Gallimard, coll. « Folio Histoire »,

- Bottéro, Jean (15 June 1995). Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods. Translated by Bahrani, Zainab; Van de Mieroop, Marc. University of Chicago Press.

- Edzard, Dietz Otto; 2004. Geschichte Mesopotamiens. Von den Sumerern bis zu Alexander dem Großen, München,

- Hrouda, Barthel and Rene Pfeilschifter; 2005. Mesopotamien. Die antiken Kulturen zwischen Euphrat und Tigris. München 2005 (4. Aufl.),

- Joannès, Francis; 2001. Dictionnaire de la civilisation mésopotamienne, Robert Laffont.

- Korn, Wolfgang; 2004. Mesopotamien – Wiege der Zivilisation. 6000 Jahre Hochkulturen an Euphrat und Tigris, Stuttgart,

- Matthews, Roger; 2005. The early prehistory of Mesopotamia – 500,000 to 4,500 BC, Turnhout 2005,

- Oppenheim, A. Leo; 1964. Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a dead civilization. The University of Chicago Press: Chicago and London. Revised edition completed by Erica Reiner, 1977.

- Pollock, Susan; 1999. Ancient Mesopotamia: the Eden that never was. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- Postgate, J. Nicholas; 1992. Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the dawn of history. Routledge: London and New York.

- Roux, Georges; 1964. Ancient Iraq, Penguin Books.

- Silver, Morris; 2007. Redistribution and Markets in the Economy of Ancient Mesopotamia: Updating Polanyi, Antiguo Oriente

- Pingree, David (1998). “Legacies in Astronomy and Celestial Omens”. In Dalley, Stephanie (ed.). The Legacy of Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press.

- Stager, L. E. (1996). “The fury of Babylon: Ashkelon and the archaeology of destruction”. Biblical Archaeology Review. 22 (1).

- Stol, Marten (1993). Epilepsy in Babylonia. Brill Publishers.

- Louvre Museum

- Vatican Museums

- British Museum

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Rijksmuseum

- Ashmolean Museum

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Field Museum of Natural History