Sumiran literature

documented a group of

some five thousand tablets discovered in south of Iraq Mesopotamia and fragments inscribed with a varied assortment of literary works have also been unearthed, and these enable us to penetrate to a certain extent into their very hearts

and souls the Sumerian belles-lettres rank high

among the aesthetic creations of civilized man. They compare the Akkadians Assyrians and Babylonians, took these works over almost in toto.

The Hittites, Hurrians, and Canaanites translated some of them into their own languages and no doubt imitated them widely The form and content of the Hebrew literary works and to a certain extent even those of the ancient Greeks were profoundly influenced by them As practically the oldest written literature of any significant amount ever uncovered

the lesser gods known collectively as the Anunnaki. Following a

brief five-line passage which tells of the Anunnaki’s homage to

Enki, Enki, for a second time, utters a paean of self-glorification.

He begins by exalting the power of his word and command in

providing the earth with prosperity and abundance, continues

with a description of the splendor of his shrine, the Abzu, and

concludes with an account of his joyous journey over the marsh-

Following another fragmentary passage whose contents are alto-

gether uncertain, we find Enki in his boat once again. With the

sea creatures doing homage to him and abundance prevailing

in the universe, Enki is ready to “decree the fates/’ Beginning,

as might have been expected, with Sumer itself, he first exalts

it as a chosen, hallowed land with “lofty

me where the gods have taken up their abode, then blesses its

flocks and herds, its temples and shrines. From Sumer he pro-

ceeds to Ur, which he extols in lofty, metaphorical language and

blesses with prosperity and pre-eminence. From Ur he goes to

Meluhha and blesses it most generously with trees and reeds,

oxen and birds, gold, tin, and bronze. He then proceeds to pro-

vide Dilmun with some of its needs. He is very unfavorably dis

Leaving farm, field, and house, Enki turns to the high plain,

covers it with green vegetation, multiplies its cattle, and makes

Sumugan, “the king of the mountains,” responsible for them. He

next erects stalls and sheepfolds, supplies them with the best fat

and milk, and appoints the shepherd-god, Dumuzi, to take charge

of them. Enki then fixes the “borders”—presumably of cities and

states—sets up boundary stones, and places the sun-god, Utu, “in

charge of the entire universe/’ Finally, Enki attends to “that

which is woman’s task/’ in particular the weaving of cloth, and

puts Uttu, the goddess of clothing, in charge.

The myth now takes a rather unexpected turn, as the poet in-

troduces the ambitious and aggressive Inanna, who feels that she

has been slighted and left without any special powers and pre-

rogatives. She complains bitterly that Enlil’s sister, Aruru (alias

Nintu), and her (Inanna’s) sister-goddesses, Ninisinna, Ninmug,

Nidaba, and Nanshe, have all received their respective powers

and insignia, but that she, Inanna, has been singled out for neg-

lectful and inconsiderate treatment. Enki seems to be put on the

defensive by Inanna’s complaint, and he tries to pacify her by

pointing out that she actually does have quite a number of special

insignia and prerogatives—”the crook, staff, and wand of shep-

herdship”; oracular responses in regard to war and battle; the

weaving and fashioning of garments; the power to destroy the

“indestructible” and to make the “imperishable” perish—as well

as by giving her a special blessing. Following Enki’s reply to

Inanna, the poem probably closes with a four-line hymnal passage

to Enki.

Here now is the translation of the extant text of the poem The poem is in the next post

Mousa Alsaibawi

The poem from Inanna ends with a four-line hymn stanza To Enki.

Enki is the Sumerian god of water, knowledge

He was later known as Ea He is the leader of the Anunnaki

Inana

Sumerian fertility goddess associated with dates, wool, meat, grain, thunderstorms and rain; later identified with Ishtar (q.v.), goddess of war and sexual love.

Inanna, the poem probably closes with a four-line hymnal passage

to Enki.

Here now is the translation of the extant text of the poem

(omitting, however, the first fifty lines, which are fragmentary

and obscure).

When father Enki comes out into the seeded Land, it brings forth

fecund seed,

When Nudimmud comes out to my fecund ewe, it gives birth to the

lamb,

When he comes out to my “seeded” cow, it gives birth to the fecund

calf,

When he comes out to my fecund goat, it gives birth to the fecund kid,

When you have gone out to the field, to the cultivated field,

You pile up heaps and mounds on the high plain,

[You] … . the .. . of the parched (?) earth.

Enki, the king of the Abzu,

Abzu : the name for fresh water from underground aquifers which was given a religious fertilising quality in Sumerian and Akkadian mythology. Lakes, springs, rivers, wells, and other sources of fresh water were thought to draw their water from the abzu. In Sumerian and Akkadian mythology, it is referred to as the primeval sea below the void space of the underworld (Kur) and the earth (Ma) above

overpowering (?) in his majesty, speaks up

with authority:

“My father, the king of the universe,

Brought me into existence in the universe,

My ancestor, the king of all the lands,

Gathered together all the trie’s, placed the me’s in my hand.

From the Ekur, the house of Enlil,

( Ekur is described in the Lament for Ur. In mythology, the Ekur was the centre of the earth and location where heaven and earth were united. It is also known as Duranki and one of its structures is known as the Kiur (“great place”)

I brought craftsmanship to my Abzu of Eridu.

I am the fecund seed, engendered by the great wild , I am the first

born son of An,

An Sumerian: 𒀭 An was the divine personification of the sky, king of the gods, and ancestor of many of the deities in ancient Mesopotamian religion. He was regarded as a source of both divine and human kingship, and opens the enumerations of deities in many Mesopotamian texts.

I am the ‘great storm’ who goes forth out of the great below/ I am

the lord of the Land,

I am the gugal of the chieftains, I am the father of all the lands,

I am the *big brother of the gods, I am he who brings full prosperity,

I am the record keeper of heaven and earth,

I am the ear and the mind (?) of all the lands,

I am he who directs justice with the king An on An’s dais,

I am he who decrees the fates with Enlil in the mountain of wisdom/

He placed in my hand the decreeing of the fates of the place where

the sun rises/

I am he to whom Nintu pays due homage,

I am he who has been called a good name by Ninhursag,

I am the leader of the Anunnaki,

I am he who has been born as the first son of the holy An/’

After the lord had uttered (?) (his) exaltedness,

After the great prince had himself pronounced (his) praise,

The Anunnaki came before him in prayer and supplication:

“Lord who directs craftsmanship,

Who makes decisions, the glorified; Enki, praise!”

For a second time, because of (his) great joy,

Enki, the king of the Abzu, in his majesty, speaks up with authority:

1 am the lord, I am one whose command is unquestioned, I am the

foremost in all things,

At my command the stalls have been built, the sheepfolds have been

enclosed,

When I approached heaven a rain of prosperity poured down from

heaven,

When I approached the earth, there was a high flood,

When I approached its green meadows,

The heaps and mounds were pi [led] up at my word

Adapa

Don’t you want to be immortal? Alas for downtrodden people!”

Adapa, the first of the antediluvian sages, is equated by some modern scholars with the biblical Adam. In the epic he rovokes the divine wrath and is summonef before the heavenly tribunal, where he is offered the bread of life. He refuses, and mankind loses the opportunity to win immortality as did Adam when, in the Garden of Eden, he failed to eat from the tree of life and instead tasted the forbidden fruit. The story breaks off when Adapa returns to earth still a mere mortal.

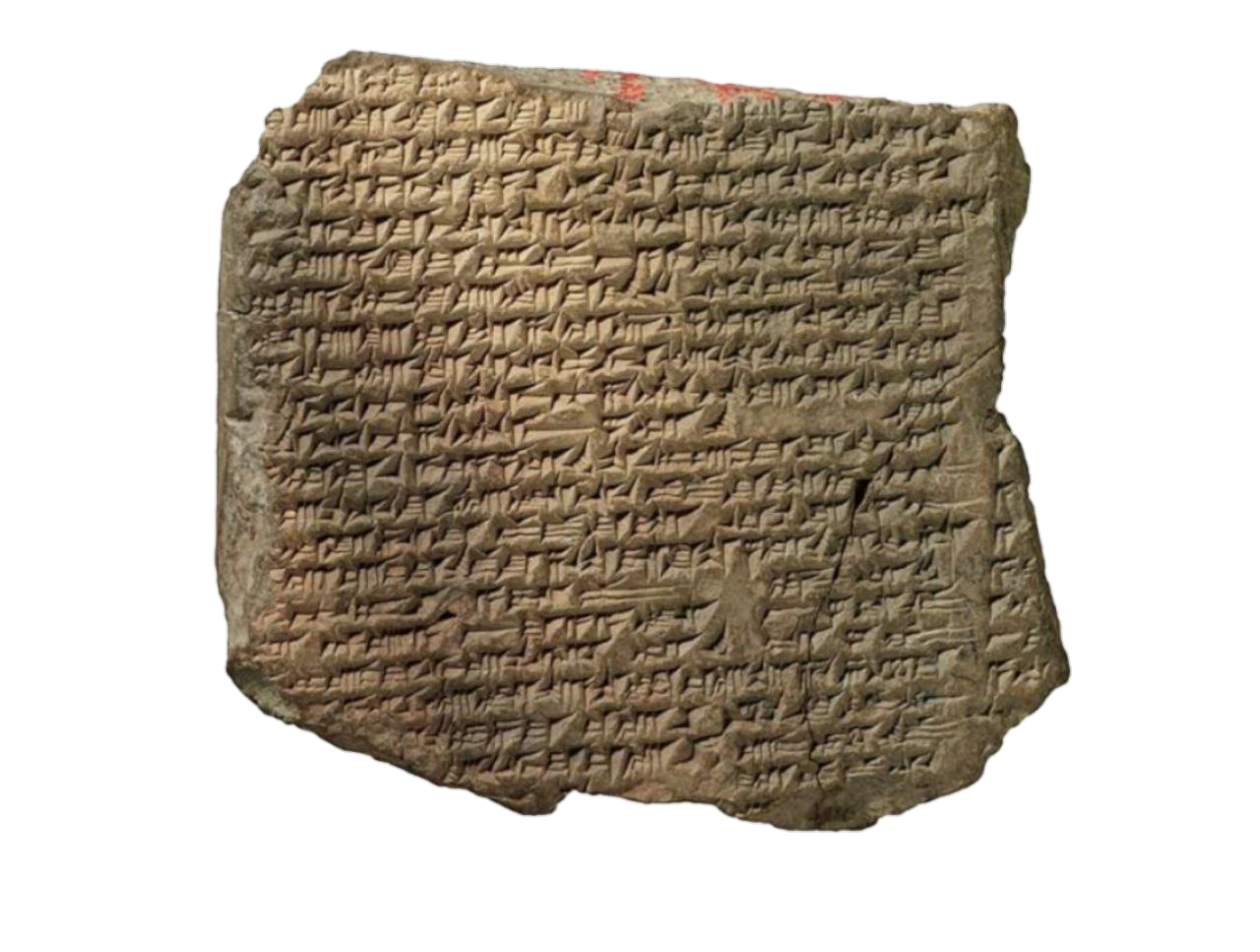

Tablet Inscribed in Akkadian

Mesopotamia iraq Nineveh, Neo-Assyrian period ca. seventh century

He (the god Ea) made broad understanding perfect in him (Adapa) to disclose the design of the land. To him he gave wisdom, but did not give eternal life … (The god Anu’s) heart was appeased, he grew quiet. “Why did Ea disclose to wretched mankind The ways of heaven and earth, Give them a heavy heart?… What can we do for him? Fetch him the bread of (eternal) life and let him eat.” “Come, Adapa, why didn’t you eat? Why didn’t you drink? Don’t you want to be immortal? Alas for downtrodden people!”

Alapa, the first of the antediluvian sages, is equated by some modern scholars with the biblical Adam. In the epic he rovokes the divine wrath and is summonef before the heavenly tribunal, where he is offered the bread of life. He refuses, and mankind loses the opportunity to win immortality as did Adam when, in the Garden of Eden, he failed to eat from the tree of life and instead tasted the forbidden fruit. The story breaks off when Adapa returns to earth still a mere mortal.

Adapa, in Mesopotamian mythology, legendary sage and citizen of the Sumerian city of Eridu, the ruins of which are in southern Iraq. Endowed with vast intelligence by Ea (Sumerian: Enki), the god of wisdom, Adapa became the hero of the Sumerian version of the myth of the fall of man. The myth relates that Adapa, in spite of his possession of all wisdom, was not given immortality. One day, while he was fishing, the south wind blew so violently that he was thrown into the sea. In his rage he broke the wings of the south wind, which then ceased to blow. Anu (Sumerian: An), the sky god, summoned him before his gates to account for his behaviour, but Ea cautioned him not to touch the bread and water that would be offered him. When Adapa came before Anu, the two heavenly doorkeepers Tammuz and Ningishzida interceded for him and explained to Anu that as Adapa had been endowed with omniscience he needed only immortality to become a god. Anu, in a change of heart, then offered Adapa the bread and water of eternal life, which he refused to take. Thus mankind remained mortal. The legend is preserved among the cuneiform tablets discovered during the 19th century in Ashurbanipal’s library at Nineveh.

Our Sources :

History Begins at Sumer (Philadelphia, 1956), Thirty Nine Firsts in Recorded History, by Samuel Noah Kramer, in 404 searchable pdf pages.

Selected Writings of Samuel Noah Kramer, in 570 bookmarked and searchable pdf pages.

Green، M.W. (1981). “The Construction and Implementation of the Cuneiform Writing System

Samuel Noah Kramer University of Pennsylvania Press, 1972 – History – 130 pages

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1944). Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C. American Philosophical Society. Revised edition: 1961.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1981). History Begins at Sumer: Thirty-Nine Firsts in Man’s Recorded History (3 ed.). University of Pennsylvania Press. I. First edition: 1956 (Twenty-Five Firsts). Second Edition: 1959 (Twenty-Seven Firsts).

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1963). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character Samuel Noah Kramer (PDF). University of Chicago Press.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1967). Cradle of Civilization: Picture-text survey that reconstructs the history, politics, religion and cultural achievements of ancient Sumer, Babylonia and Assyria. Time-Life: Great Ages of Man: A History of the World’s Cultures..

- Wolkstein, Diane; Kramer, Samuel Noah (1983). Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer. New York: Harper & Row.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1988a). In the World of Sumer: An Autobiography. Wayne State University Press

- Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization. Paul Kriwaczek.

Ancient Mesopotamia. Leo Oppenheim.

Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History. University of Chicago.

Mesopotamia 8000-2000 B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

30,000 Years of Art. Editors at Phaidon. - Treasures of the Iraq Museum Faraj Basmachi Ministry of Information, 1976 – Art, Iraqi – 426 pages

- Algaze, Guillermo, 2008 Ancient Mesopotamia at the Dawn of Civilization: the Evolution of an Urban Landscape. University of Chicago Press

- Atlas de la Mésopotamie et du Proche-Orient ancien, Brepols, 1996

- Bottéro, Jean; 1987. (in French) Mésopotamie. L’écriture, la raison et les dieux, Gallimard, coll. « Folio Histoire »,

- Bottéro, Jean (15 June 1995). Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods. Translated by Bahrani, Zainab; Van de Mieroop, Marc. University of Chicago Press.

- Edzard, Dietz Otto; 2004. Geschichte Mesopotamiens. Von den Sumerern bis zu Alexander dem Großen, München,

- Hrouda, Barthel and Rene Pfeilschifter; 2005. Mesopotamien. Die antiken Kulturen zwischen Euphrat und Tigris. München 2005 (4. Aufl.),

- Joannès, Francis; 2001. Dictionnaire de la civilisation mésopotamienne, Robert Laffont.

- Korn, Wolfgang; 2004. Mesopotamien – Wiege der Zivilisation. 6000 Jahre Hochkulturen an Euphrat und Tigris, Stuttgart,

- Matthews, Roger; 2005. The early prehistory of Mesopotamia – 500,000 to 4,500 BC, Turnhout 2005,

- Oppenheim, A. Leo; 1964. Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a dead civilization. The University of Chicago Press: Chicago and London. Revised edition completed by Erica Reiner, 1977.

- Pollock, Susan; 1999. Ancient Mesopotamia: the Eden that never was. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- Postgate, J. Nicholas; 1992. Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the dawn of history. Routledge: London and New York.

- Roux, Georges; 1964. Ancient Iraq, Penguin Books.

- Silver, Morris; 2007. Redistribution and Markets in the Economy of Ancient Mesopotamia: Updating Polanyi, Antiguo Oriente

- Pingree, David (1998). “Legacies in Astronomy and Celestial Omens”. In Dalley, Stephanie (ed.). The Legacy of Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press.

- Stager, L. E. (1996). “The fury of Babylon: Ashkelon and the archaeology of destruction”. Biblical Archaeology Review. 22 (1).

- Stol, Marten (1993). Epilepsy in Babylonia. Brill Publishers.

- Louvre Museum

- Vatican Museums

- British Museum

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Rijksmuseum

- Ashmolean Museum

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Field Museum of Natural History