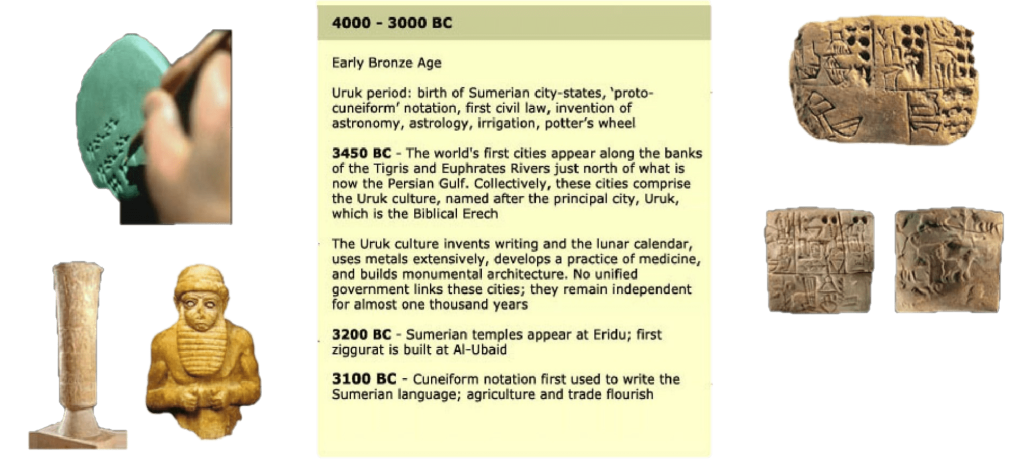

Historical Ages

Towards the beginning of the third millennium B.C., a few dynastic states emerged in various cities of South Mesopotamia, each consisting of an independent city-state ruled by a king. Simultaneously, writing was further developed and became more suitable for keeping records and conveying information. The ruling kings and princes began to record on clay and stone tablets their deeds and victories. Hence, at this date, we may say that the ‘Historical Period’ dawned in the region, and with it we enter the Early Dynastic or the City-State Period. Many qualified specialists and historians have written about the historical and prehistoric periods of ancient Iraq, and the works mentioned in Bibliography, which provide thorough and penetrating view of the subject, are especially recommended to readers.

Sumerian Early Dynastic Period :

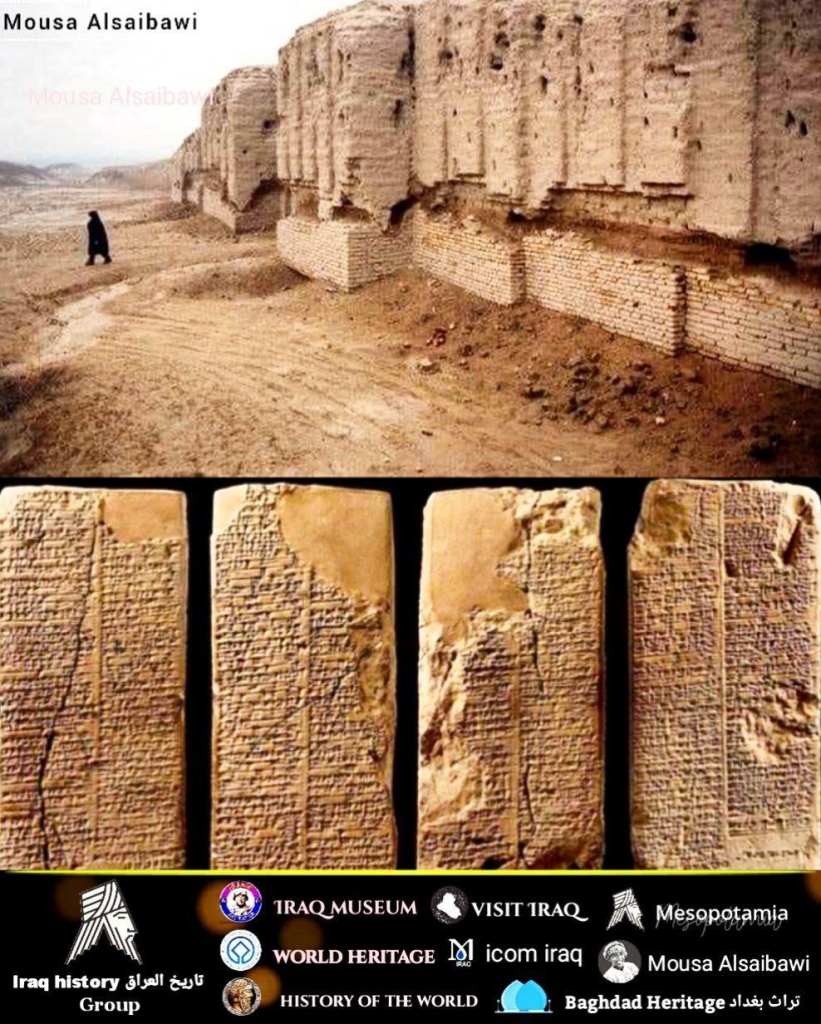

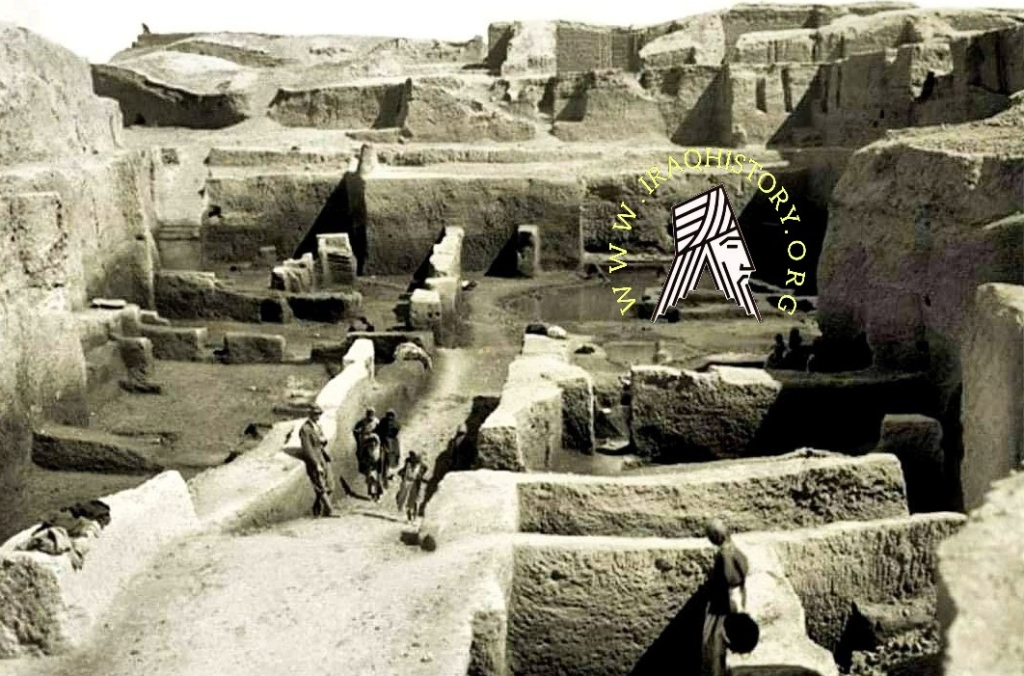

The Early Dynastic Period lasted from the end of the Jamdat Nasr Period (c. 2900B.C.) till the Sargonid Akkadian Empire (c. 2350 B.C.). This period saw important social and cultural developments and its remains are found in strength at such famous cities as Sippar (modern Abu Habba), Shuruppak (Fara), Kish (Tell al-Uhaimir), Uruk (Warka),Ur (Muqayyar), Nippur (Nuffar), Girsu (Telloh), Lagash (Al-Hiba), Khafaje, Tell Ajrab and Mari (Tell Hariri). These cities, whose ruins and monuments continue to exist to the present day, bearing witness to the grandeur of their achievement, were prosperous urban centres with great palaces, temples and fortification walls, surrounded by orchards and fields irrigated by canals and streams.

Nippur (Sumerian: Nibru ) often logographically recorded as 𒂗𒆤𒆠 “Enlil City”

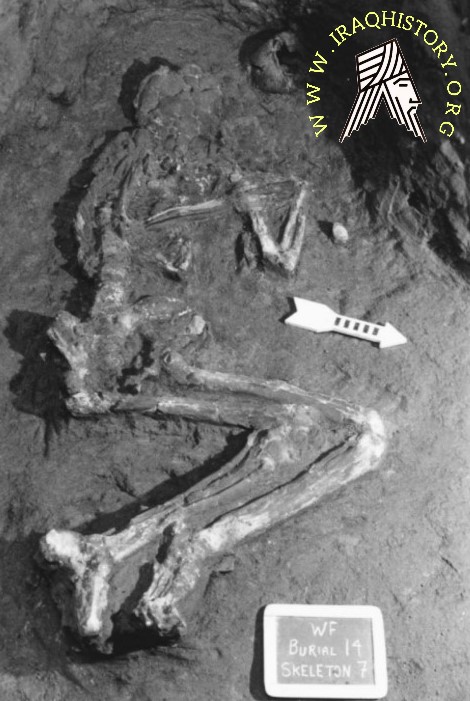

Skeletal remains Discovered in Nippur

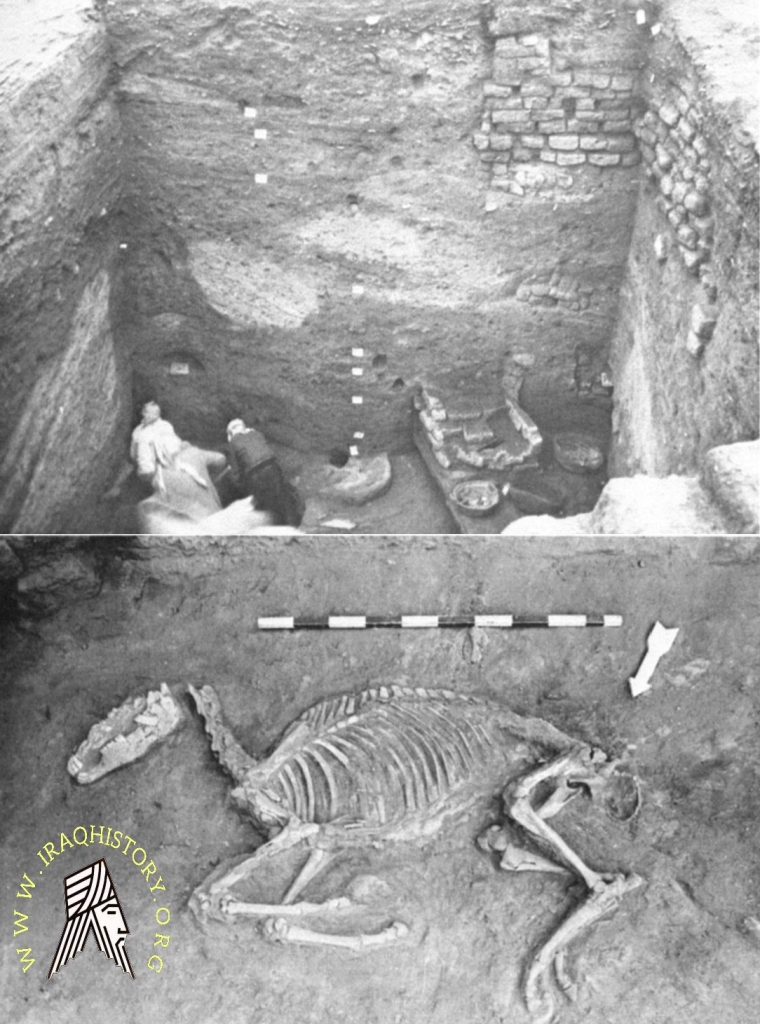

Nevertheless, feuds and conflicts between the city-states continued throughout. Archaeological excavations have produced magnificent artifacts which bear witness to their social, cultural, and religious life.

The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago’s Expedition, digging in the Diyala region

made many discoveries which increased our knowledge of the Early Dynastic Period2. The finds included statuary representing the gods, kings and dignitaries, and many stamp seals and cylinder seals and plaques or slabs of stone on which figure mythological, religious and historical scenes, including relief scenes of the New Year’s celebrations.

The archaeological remains of the Early Dynastic Period also include characteristic types of pottery.

of the Early In view of the long space of time-exceeding five hundred years Dynastic Period, and the abundance of its artifactual material and monumental mains,

archaeologists have proposed to divide it into three stages, I to III

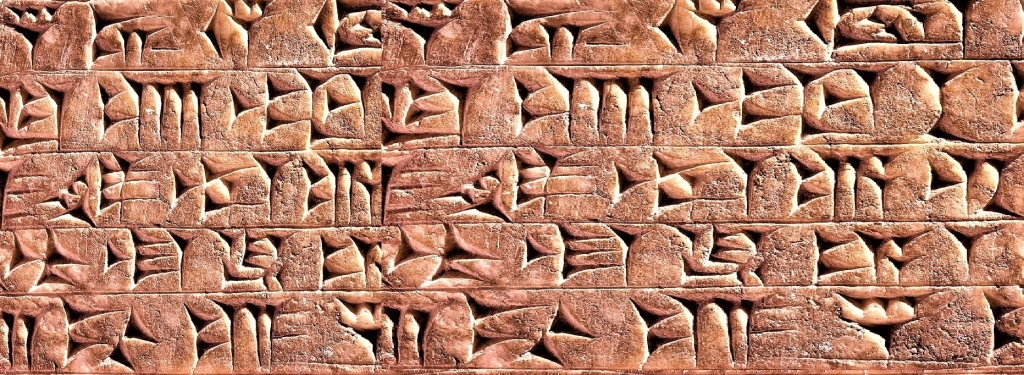

distinguished by their characteristic architectural and technological features. The inhabitants of these city-states were predominantly Sumerians (though other ethnic groups were represented who had inhabited the land in the fifth millennium B.C. and developed a prehistoric culture that prepared the ground for the historical Early Dynastic Periods). From inscriptions they left behind we know that the predominant element of the population were the ‘Sumerians’, who spoke the Sumerian language which is entirely different from the Semitic language that spread later. During this period, Sumerian writing developed from mere pictographic signs into phonetic syllables written on clay or carved on stone in horizontal lines.

By means of these wedge-shaped symbols known cuneiform and totaling some600 known signs, syllables and words could be expressed and they were used to inscribe records of events, myths,incantations etc.

Later, in about 2000 B.C., Sumerian and Babylonian writers collected what they could of these inscribed documents with their chronicles, stories and historical details. They left us King Lists and records of dynasties compiled in successive order which cannot, of course, be accepted uncritically, as the information given is either incomplete or imprecise, due to the long space of time which elapsed between the events themselves and the written records of them. We find, for example, that these writers omitted some important dynasties as well as over-estimating the years of some rulers, probably in view of their affinity to the gods and to their mythical character. Some dynasties we also find listed in successive order although we know they existed simultaneously. But excavations in ancient cities and the discoveries of archaic texts, the decipherment of cuneiform writing and the advance of archaeology continue to supply archaeologists, with more information on the Early

Dynastic Period. In the following pages I shall attempt to reconstruct in brief outline the sequence of events during the Early Dynastic Period. For the King Lists, illustrating the succession of ruling dynasties, the reader is referred to Part II where the complete lists are given.

(( Antediluvial Kings ))

The Sumerian King List dating back to ca. 2000 B.C.” records that before the Flood eight kings had reigned in five cities to which Kingship was lowered from heaven cording to Sumerian tradition. The first of these kings reigned in Eridu. Their reign, again according to Sumerian figures, lasted about a quarter of a million years before the Deluge came. Excavations in many ancient cities of South Mesopotamia have yielded traces of a flood. After the flood, again Kingship was lowered from heaven’, this time in Kish.

kish and the Sumerian King List (Image Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford)

This clay prism is one of the most important records from ancient Mesopotamia Iraq

In this way the rulers of the city of Isin legitimized themselves as the rightful successors of powerful kingdoms of the past

Each of the four sides is inscribed with two columns of cuneiform (wedge-like) script recording the Sumerian language. The document lists a succession of cities in Sumer and its neighboring regions, their rulers and the length of their reigns. Several versions of the Sumerian King List have survived, but this one represents the most extensive as well as the most complete.

The list is not history as we would understand it, but a combination of myth, legend and historical information. It starts with the mythological origins of kingship, when individuals have fantastically long reigns. This is followed by the famous lines: ‘The Flood swept over. After the Flood had swept over and kingship had descended from heaven’. The flood is the subject of other major works in Mesopotamian literature and the story was adapted in the Old Testament to form the basis of the account of Noah.

As the list reaches historical rulers the length of each reign becomes more realistic. It ends with King Sin-magir of the so-called Isin dynasty (around 1827–1817 BC). The Sumerian King List seems to have been composed to imply that the dominion of Mesopotamia, determined by the gods, could only be exercised by one city at a given time and for a limited period. In this way the rulers of the city of Isin legitimized themselves as the rightful successors of powerful kingdoms of the past

The Sumerian dynasties are divided as :

1- First Dynasty of Kish :

According to the King List, the first Dynasty of Kish comprised 23 monarchs; the last of them was Agga who we know to have reigned ca. 2560 B.C., and who is famous in legend as having done battle with the fifth king of Uruk, Gilgamesh. The Sumerian poem Gilgamesh and Aga records the Kishite siege of Uruk after its lord Gilgamesh refused to submit to Aga, ending in Aga’s defeat and consequently the fall of Kish’s hegemony.

Kish is one of the most important major cities for the Sumerians, according to Sumerian mythology. It was the first city to have a king after the Great Flood. Ziusudra is supported by his being a king from Shuruppak through the Gilgamesh Tablet XI, a reference to Utnapishtim (an Akkadian translation of the Sumerian name Ziusudra). ) with the title of Shuruppak Man in line 23

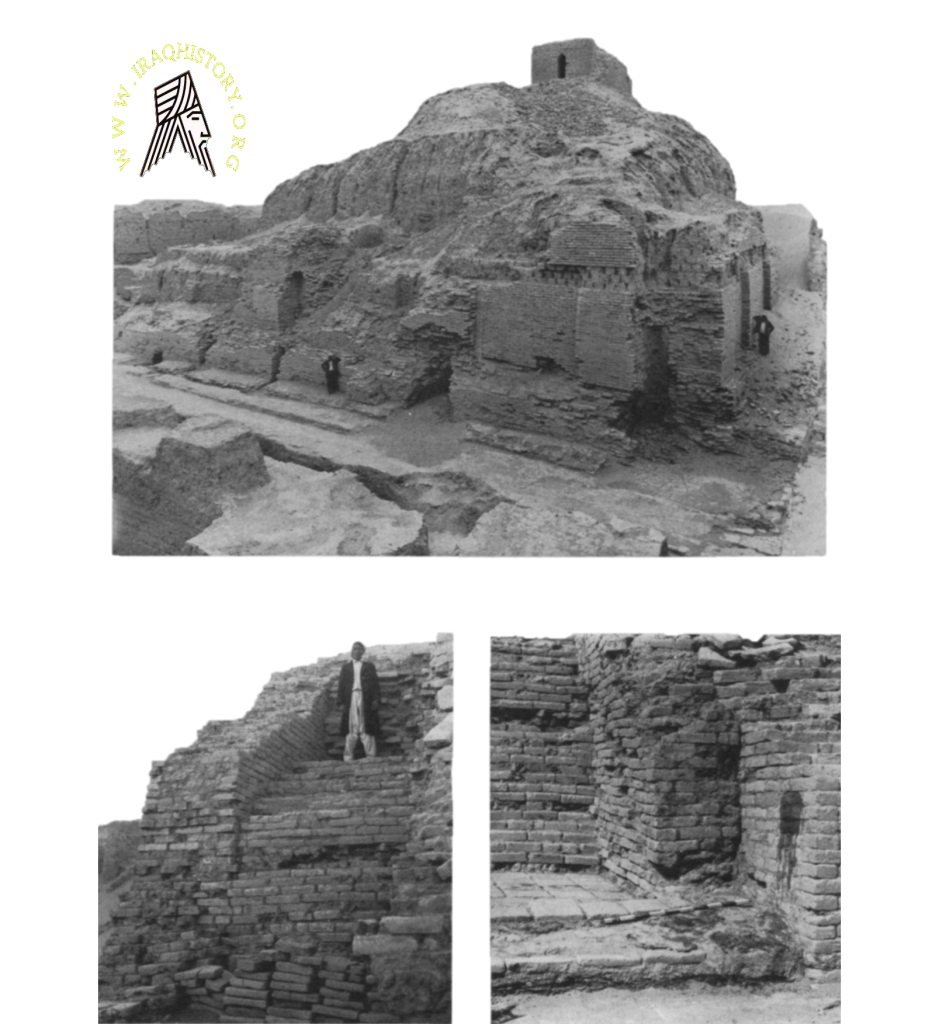

The city of kish iraq

2 -First Dynasty of Uruk :

According to the king List the First Dynasty of Uruk comprised 12 reigns, and the names of some of its monarchs are told to us in the old tales or legends inscribed on Sumerian literary tablets. Prominent among these are Lugalbanda, the divine shepherd, Dumuzi, the vegetation god, and Gilgamesh, the legendary hero of the famous epic of Gilgamesh’, who reigned in 2675 B.C. and defeated Agga, the last king of the First Dynasty of Kish. Among the deeds attributed to Gilgamesh are the Epic of Gilgamesh, the first literary epic in history, the building of Uruk’s fortification walls and the erection of some of its temples.

3 – First Dynasty of Ur :

The kings of the first dynasty of Ur continued for 177 years. Among the famous names are King Mes-anne-padda 𒈩𒀭𒉌𒅆𒊒𒁕 (ac. 2475 B.C.) and his son King A-anne-padda, who dedicated to the goddess Nin-hursag 𒀭𒎏𒄯𒊕 a large temple at al-Ubaid.

figures cut from shell, limestone or copper and fitted to its background with black bituminous shale; the surviving remains include a scene of milking cattle, churning and storing the milk. The main doorway is flanked by mosaic columns of which specimens can be seen erected in Hall III of the Irag Museum.

Towards the end of this dynasty, or rather in the time of its kings Elulu and his son Balulu, while other dynasties were in fierce conflict for power, an Elamite dynasty emerged at Awan and brought under its control a large area of Eastern Sumer. Another strong dynasty had its seat at Mari (Tell Hariri) on the Middle Euphrates, and Kish achieved sovereign power. At one point also, Eannatum, King of Lagash, controlled most of the cities in the south and, as will be detailed later, annexed them to his empire.

The temple façade is decorated with beautiful ornamental friezes inlaid with animal

The Tell alUbaid Copper Lintel or Imdugud Relief is a large copper panel found at the ancient Sumerian city of Tell al-Ubaid in southern Iraq. Excavated by the English archaeologist Henry Hall in 1919, the frieze is one of the largest metal sculptures to survive from ancient Mesopotamia and is now preserved in the British Museum

3- Second Dynasty of Kish :

The second dynasty of Kish was represented by eight kings of whom the earliest.

ones synchronized with the kings of Uruk and Ur. The fourth king of this dynasty album, routed from the country the Elamite dynasty of Awan. An important work of art from Tello (now in the Louvre Museum in Paris) is a sculptured mace head engraved for Mesilim, one of the titular kings of Kish, whose reign must be placed within this period (ca. 2600 B.C.) though omitted by the Sumerian King List. The great exploits of this monarch won him a supreme place among the kings of this dynasty. His activities extended to the central and eastern regions of the country, and Lagash, and probably other great cities in the South, owed allegiance to him.

During his reign the antagonism between Umma and Lagash was halted after he stepped in as arbitrator, drew up a treaty between the two states and set up a stele of delimitation between their territories. Later, this dynasty of Kish also weakened, and anew Elamite dynasty named Hamazi emerged on the highlands which border Iraq to the east and their armies descended westward and imposed their law upon some Sumerian cities including Nippur.

4- Lagash Dynasty ;

The strong Dynasty of Lagash comprised ten reigns with a total duration of 165years (ca. 2520-2355 B.C.). The monuments and inscriptions from Tello (ancient Girsu in the land of Lagash) have made it possible to reconstruct in some detail the history of Lagash in the middle of the 3rd millennium B.C. Surprisingly, however, the rulers of this dynasty did not figure in the Sumerian King List although historians have definitely ascertained that this powerful dynasty exercised suzerainty over a large part of south Iraq. in alliance with the second dynasties of Uruk and Ur and the dynasty of Adab, but with higher authority in the hand of the Lagash rulers.

art and a number The Lagash period belong to the end of the Early Dynastic period. Ninety years ago a French expedition unearthed at Tello very remarkable works of inscriptions that enable us to draw up a list of Lagash (patesis)30 among whom the following names are most prominent:

Ur-Nanshe, 𒌨𒀭𒀏 the founder of the dynasty of Lagash (ca. 2520-2490 B.C.), is known for his building activities such as the restoration of temples of the god Ningirsu and the goddess Nanshe. Finely executed genealogical bas-reliefs are known representing Ur.is exhibited a limestone stele³ with relief carvings on all four sides, depicting an an-Nanshe with his children in special ceremonies, and in the Irag Museum (Halla III)) there is exhibited limestone stele with relief carvings on all four sides depicting an ancient

Sumerian goddess and a family group of Ur-Nanshe. Akurgal, his son, who

succeeded him upon the throne, campaigned against the city of Umma, but unsuccessfully. And was succeeded by his son.

Ur-Nanshe, king of Lagash, c. 2500 BCE; in the Louvre, Paris.

Akurgal Sumerian: 𒀀𒆳𒃲, “Descendant of the Great Mountain” in Sumerian was the second king (Ensi) of the first dynasty of Lagash. His relatively short reign took place in the first part of the 25th century BCE (circa 2464-2455 BCE), during the period of the archaic dynasties. He succeeded his father, Ur-Nanshe, founder of the dynasty, and was replaced by his son E-annatum During his reign, a border conflict pitted Lagash against Umma, These borders between Umma and Lagash had been fixed in ancient times by Mesilim, king (lugal) of Kish, who had drawn the borders between the two states in accordance with the oracle of Ishtaran, invoked as intercessor between the two cities

E-annatum: His reign is estimated to be around 2470 B.C. Among the monuments the famous Stele of the Vultures, now in the Louvre in Paris which this is one of the most remarkable of all Sumerian works of sculpture. It combines history and religion in its commemoration of the victory won by King Eannatum of over the town of Umma. Eannatum captured Kish and overthrew Balulu, ensi of Ur and En-akale. ensi of Umma. He was contemporary with En-shakush-anna, governor Uruk.

The Stele of the Vultures is a monument from the Early Dynastic IIIb period (2600–2350 BC) in Mesopotamia celebrating a victory of the city-state of Lagash over its neighbour Umma. It shows various battle and religious scenes and is named after the vultures that can be seen in one of these scenes. The stele was originally carved out of a single slab of limestone, but only seven fragments are known to have survived up to the present day. The fragments were found at Tello (ancient Girsu) in southern Iraq in the late 19th century and are now on display in the louvre The stele was erected as a monument to the victory of king Eannatum of Lagash over Ush, king of Umma. It is the earliest known war monument.

Enannatum: Following the conquests over Umma and the neighboring city-states during the reign of his brother Eannatum, the power of Lagash as a city-state reached its zenith at the time of Enannatum who commemorated his military achievements and the construction and restoration of the temples. But his success was threatened by the city of Mari (modern Tell Hariri on the Middle Euphrates) some of whose kings of this date left important and valuable statues and other objects which are now the pride of the Damascus Museum in Syria. Encouraged by Enannatum’s preoccupation with internal dissension and other affairs of Lagash and with holding in check the aggression of neighboring Umma, the king of Mari succeeded in capturing Ur and Uruk. Wealso learn that Enannatum died in one of these battles and was succeeded by his son Entemena.

Sumerian chariot of King Eannatum of Lagash, c. 2500 B.C.

En-temena : 𒂗𒋼𒈨𒈾 (ca. 2430-2400 B.C.) managed to rout the men of Umma from Lagash andits outskirts. Having restored to Lagash its authority and glory, the king turned toed, among other things, a silver vase delicately engraved with ornaments and inscribed-construction work and renovation of temples in the city. The excavations at Telloh yield-with a dedication to the god Ningirsu by Entemena (now among the exhibits of the diorite found at Ur (Hall III), and the chief priest and scribe, Dudu, who became known Louvre in Paris). The reign of Entemena synchronized with the reigns of Lugal-anne-at this time, is represented by a beautiful statue now in the possession of the Iraq Museum the Regin of entemena synchronized with the reigns of lugal-anne

mundu, King of Adab, En-shakush-anna, King of Uruk and Lugal-kinishe-dudu, King of Ur.

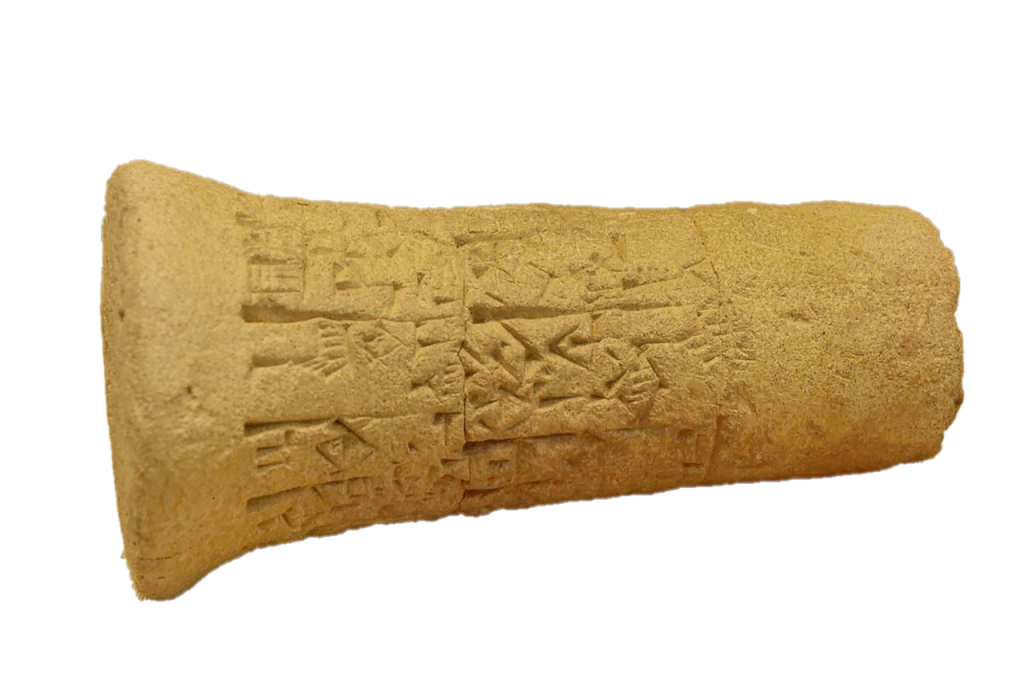

Another example of the foundation nail dedicated by Entemena, king of Lagash

The Vase of Entemena is a tripod type silver vase and was named after Entemena, the ruler of Lagash

After Entemena, weak and less successful leaders came to power in Lagash, which gave rise to dissension between religious men and the royal house, weakening the city’s power of resistance, so that Lagash had to share its authority with a few other dynasties such as the Third Dynasty of Kish, the Dynasty of Akshak and the Fourth Dynasty of Kish. The last king in the dynastic line of Lagash is Urukagina.

Urukagina : who came to power in 2355 B.C., was famous for his reforms. He regulated taxation and tax-gathering and hit hard at the corruption that existed in the ranks of his officials. He, too, interested himself in the construction and restoration of temples and he was a contemporary of Ku-bau the Queen of Kish. Urukagina was the last Old Sumerian ruler of Lagash before its conquest by Lugalzagesi of Umma and the subsequent Sargonic period. His reign witnessed a gradually shrinking sphere of political power under threat from both Uruk and Umma, that at one point forced him to abandon Lagash and move his capital to Girsu. At the same time, he instituted a well-known series of reforms that attempted to redress some of the social and economic iniquities of his day

The Reforms of UruKAgina

reserved on two complete cones and one cone fragment, the text of the so-called Reforms of UruKAgina details the transgressions of former times and the new regulations of UruKAgina. The reforms are particularly concerned with the governance of the land of the gods and rules relating to burials. The text has been seen as a forerunner to the later law-codes but is probably better seen as a royal inscription with a particular focus on the role of the king as protector of the weak.

But the weakened military organization of the state provided a favorable opportunity for the powerful king of Umma, Lugal-zaggesi, to strike at Lagash.

Lugal-zaggesi 𒈗𒍠𒄀𒋛 : the ambitious leader of Umma, after achieving the submission of Uruk, removed his seat of government from Umma Uruk, established himself as the King of Uruk, and founded the city’s Third Dynasty (ca. 2355 B.C.). After fierce wars with other city-states, he conquered the rest of Sumer and by virtue of his diplomacy was able to rule it as a confederation subject to his authority. Later he sacked Lagas hand overthrew Urukagina, the last in the dynastic line of Lagash. He left many inscriptions from which we can extract considerable information on his achievements in addition to the invocations of deities. His efforts to introduce a unified code of laws in his domains were thwarted by the rise to power of Sargon of Agade, who defeated him in battle, thus dealing a death blow to the era of the city-states. Sargon came from the Semitic element in the Mesopotamian community, called, after his own capital, the Akkadians, who had long formed a part of the population, and had been infiltrating from the Arabian Desert and the Euphrates, settling in the towns and country.

Sources :

Faraj Basmachi + Harvard University + British Museum + Iraqi Museum + Louvre Museum + University of Chicago