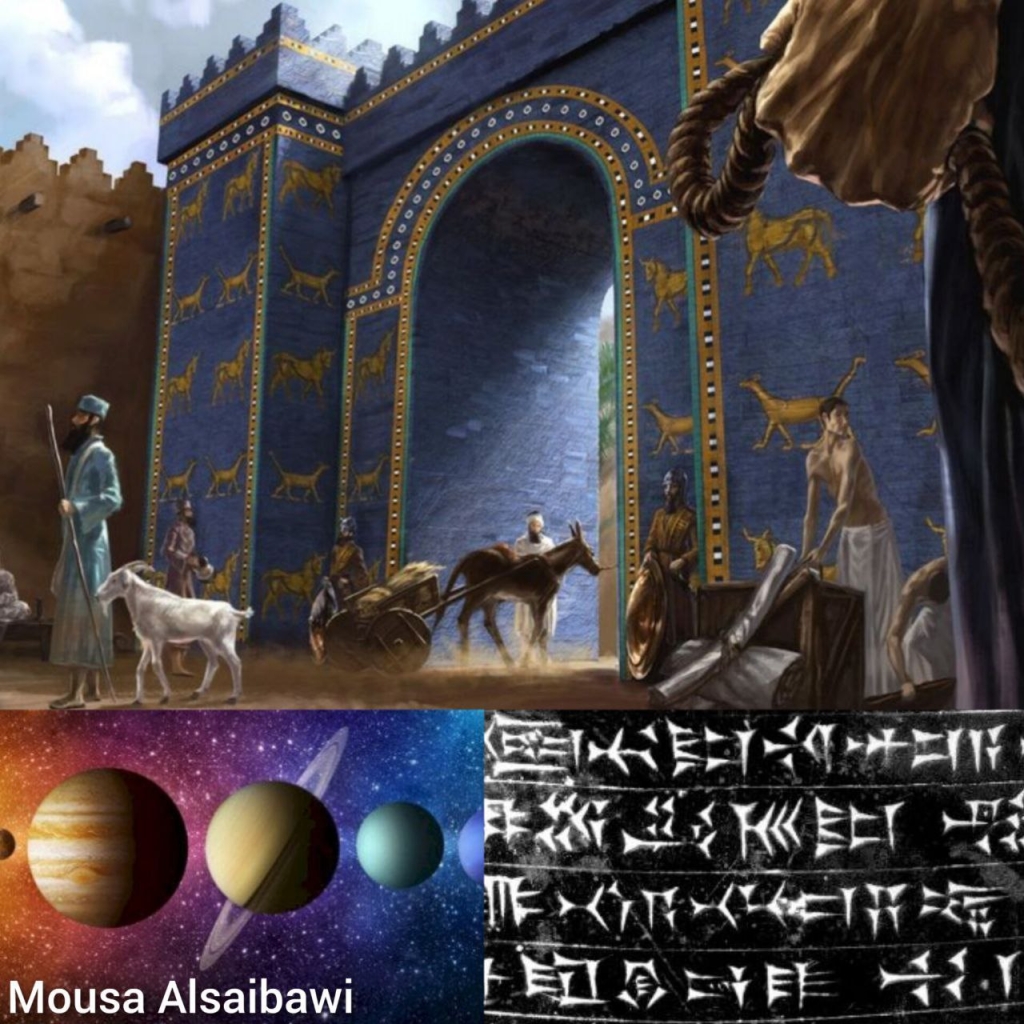

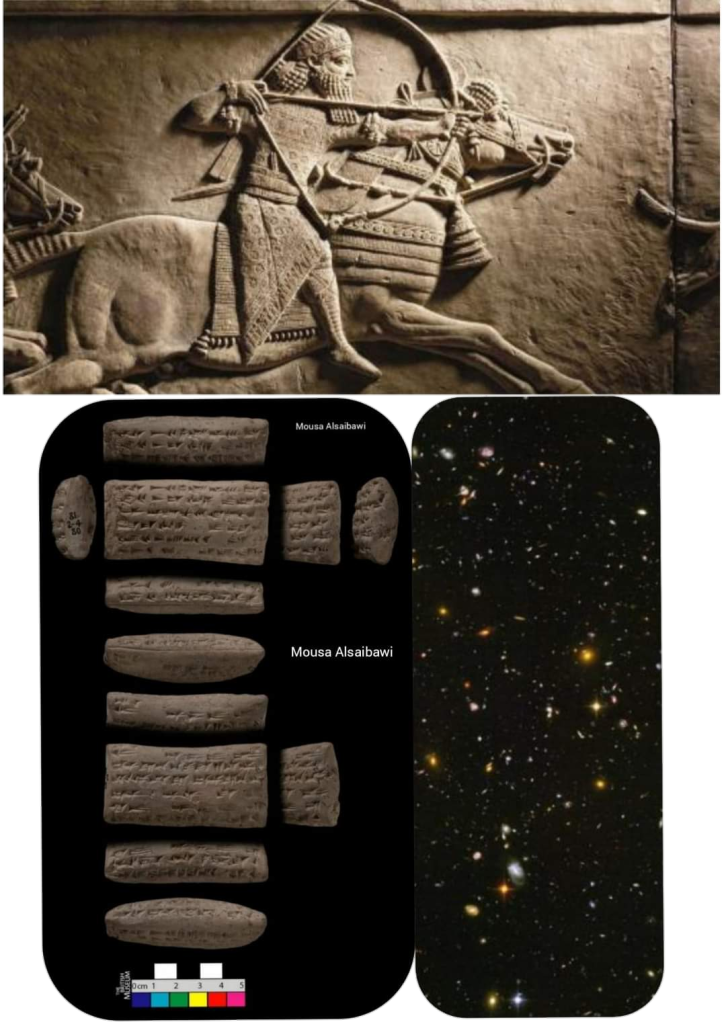

The earliest known written sources dealing with astronomy come from the regions of ancient cities of iraq Assyria and Babylonia located in what is now Iraq

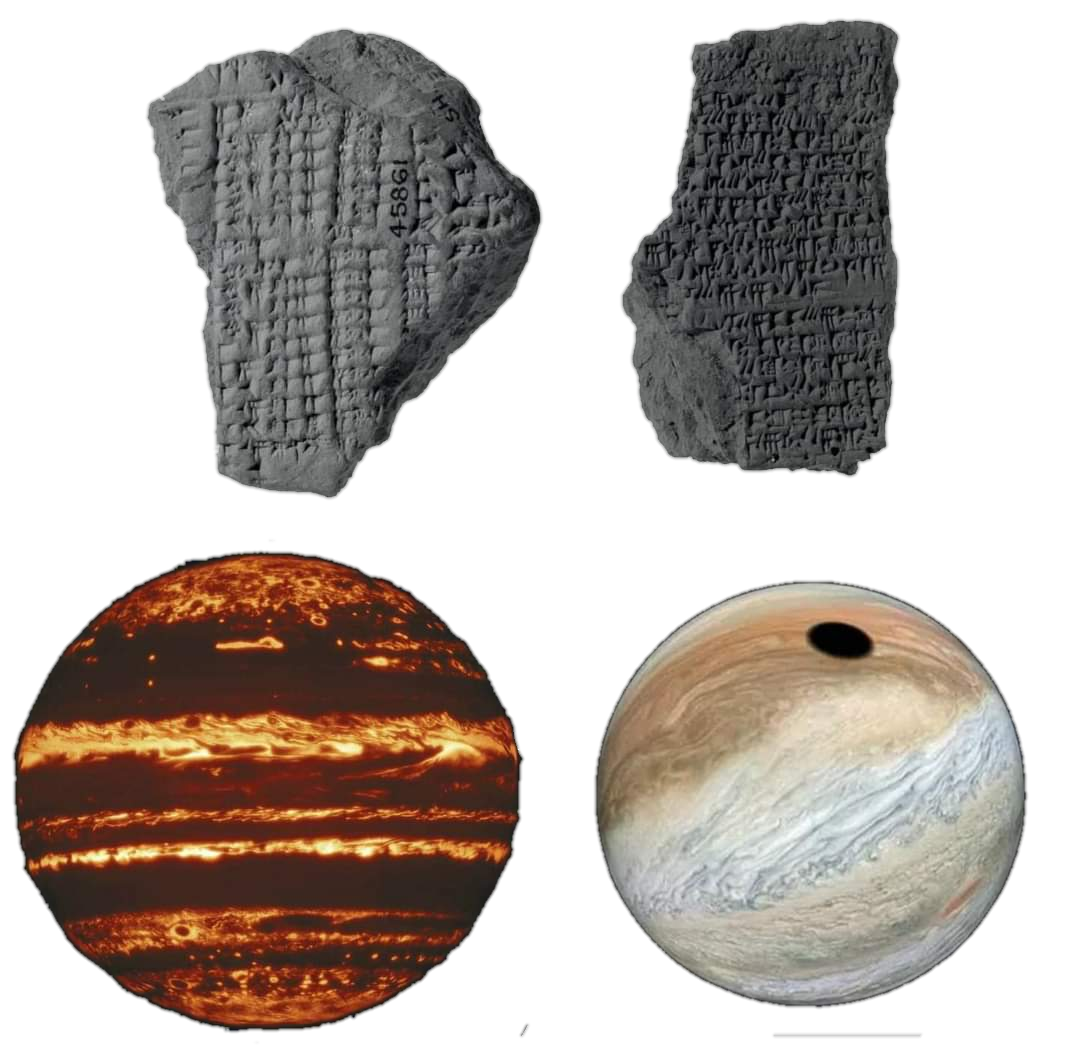

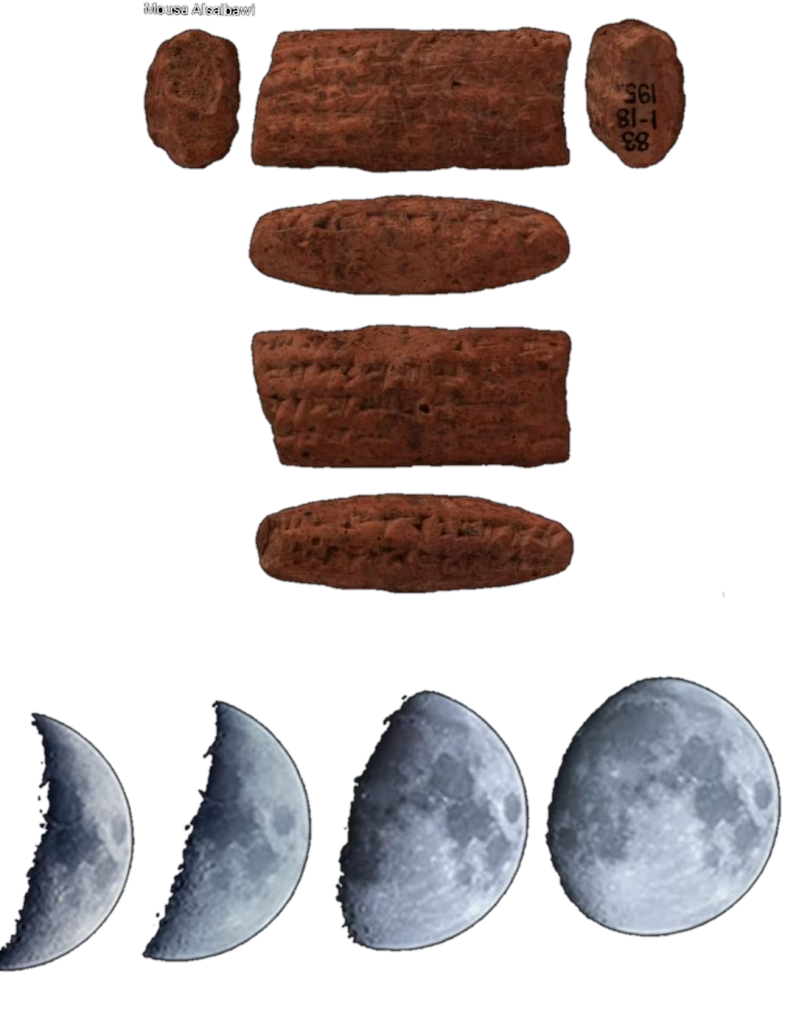

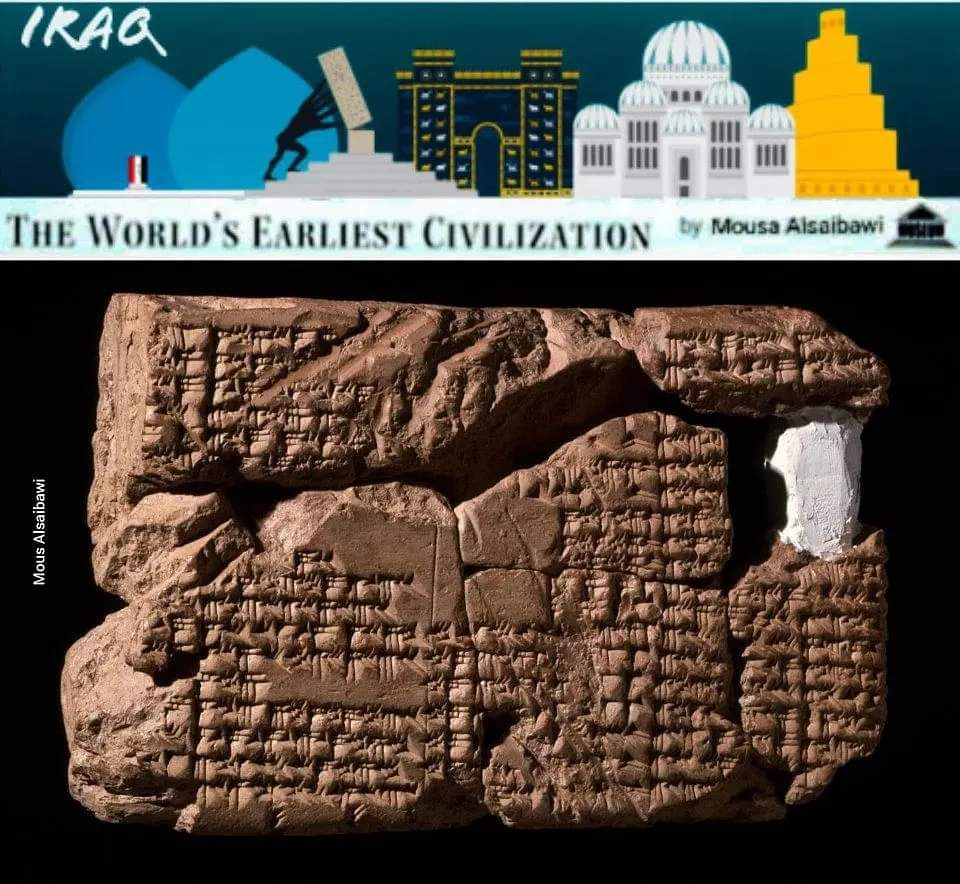

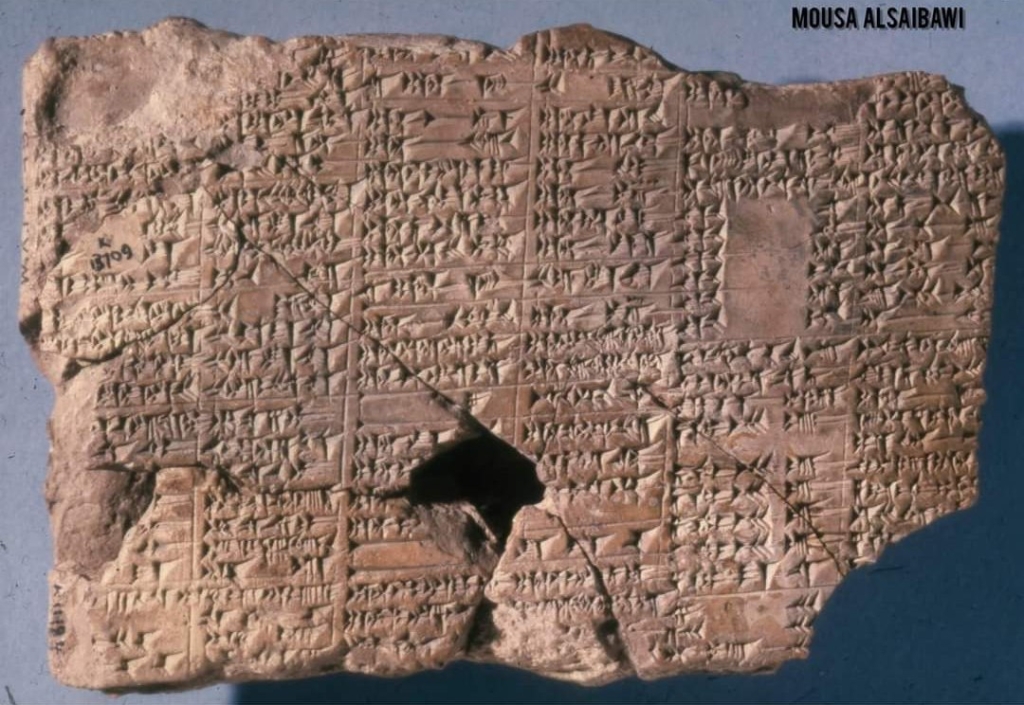

Astronomical cuneiform tablets have been recovered from a number of sites throughout Mesopotamia. Almost all preserved tablets date to the Neo-Assyrian (c. 750-600 BC) and Late Babylonian (c. 750 BC – AD 75) periods, although some are clearly copies of earlier works. From Assyria, several hundred astronomical tablets have been recovered from Nineveh, with smaller numbers found at Ashur and Nimrud. From Babylonia, more than four thousand tablets have been recovered from Babylon, a few hundred from Uruk, and a handful from each of Sippar, Nippur and Ur. Outside of Mesopotamia proper, a small number of astronomical cuneiform tablets were found at the Neo-Assyrian city of Sultantepe. and its neighbours. These sources are written in the Akkadian language using cuneiform writing on clay tablets. Because clay is a non-perishable material, especially when baked (either intentionally in an oven or in sunlight, or unintentionally in a burning building), several hundred thousand cuneiform tablets have been recovered from archaeological sites in Mesopotamia, and many more are almost certainly still in the ground. Only a small proportion of cuneiform tablets, perhaps around 1%, concern astronomy, but this translates into about 5000 tablets dealing with astronomical observation, prediction, theory and astrology. Of these 5000 tablets, probably between one half and two thirds have been studied and published; work continues on the slow process of publishing the remainder.

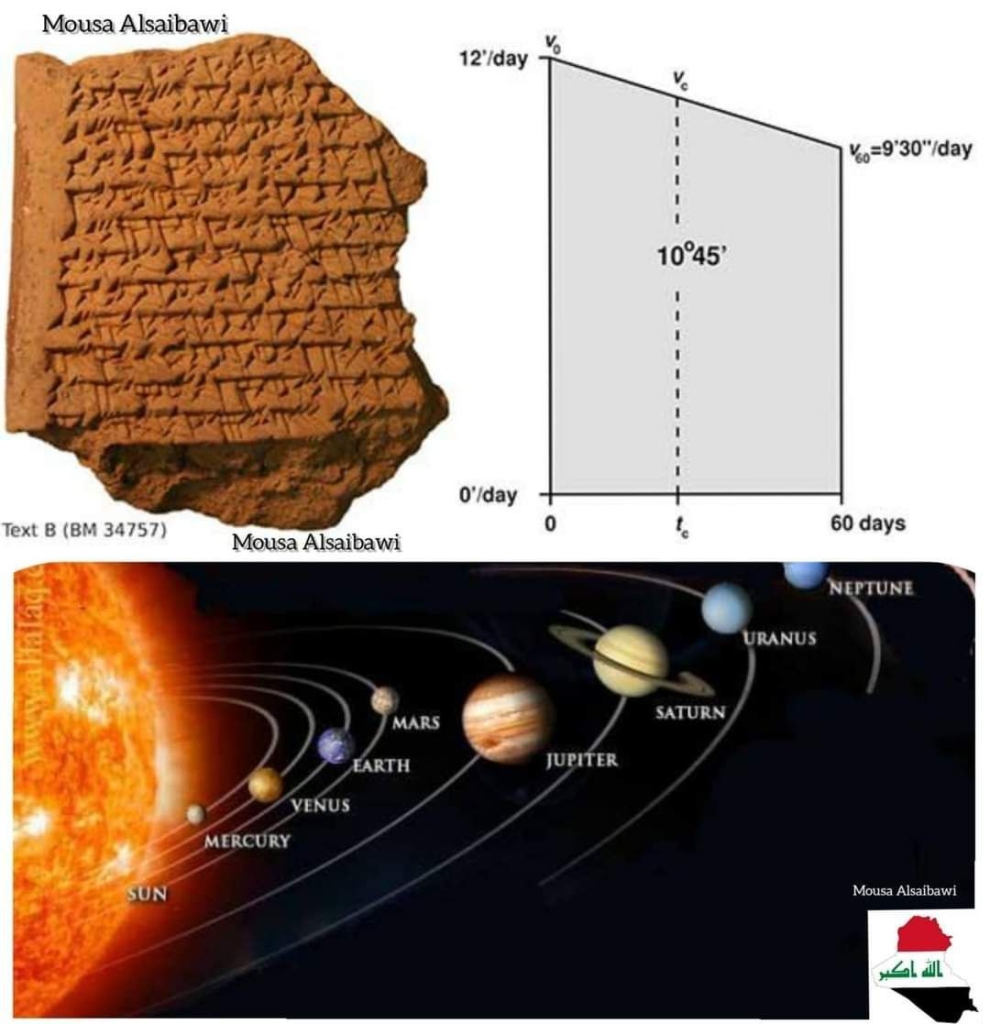

Babylonian astronomical tablet At right this diagram shows how the distance traveled by Jupiter after 60 days 10º45 is calculated as the area of the trapezoid The Babylonians knew they could then divide this trapezoid into two smaller ones of equal area in order to find the time in which Jupiter covers half the distance it travels in 60 days

Textual evidence indicates that in Mesopotamia the sun, moon, planets, and certain stars and constellations had already been named by the 3rd millennium BC. Also by this time, and quite possibly much earlier, a luni-solar calendar was in use comprising twelve lunar months which began on the evening of first lunar-crescent visibility with intercalations roughly every three years. By the Old Babylonian period (first half of the 2nd millennium BC), the earliest mathematical schemes for modelling changes in celestial phenomena (the length of day and night) had been developed. Also around this time we find the earliest celestial omens based upon the appearance of the moon during an eclipse.

Babylonians detailed their use of trapezoids to track the planet Jupiter

Prof Ossendrijver examined five Babylonian tablets that were excavated in the 19th Century, and which are now held in the British Museum’s archives.

The script reveals that they were using four-sided shapes, called trapezoids, to calculate when Jupiter would appear in the night sky, and also the speed and distance that it travelled.

“This figure – a rectangle with a slanted top – describes how the velocity of a planet, which is Jupiter, changes with time,” he said.

“We have a figure where one axis, the horizontal side, represents time, and the other axis, the vertical side, represents velocity.

“The area of trapezoid gives you the distance travelled by Jupiter along its orbit.

“What is so special is this type of graph is unknown from antiquity – so making figures of motion in this rather abstract space of velocity against time – this is something very, very new.”

He added that there was evidence that the Greeks used a “more straightforward” form of geometry, which dealt with the spatial relationships between the Earth and the planets rather than the concepts of time and velocity.

Prof Ossendrijver told the BBC that it was unclear how common this technique was.

“It could be that there was an earlier tablet, written by a genius, by one individual, who came up with this new way of doing astronomy.

“It could also be that in fact this is a method that was more widely applied by different scholars. We don’t know.”

In ancient Mesopotamia, all five planets visible to the naked eye were known and studied, along with the Moon, the Sun, the stars, and other celestial phenomena. In all Mesopotamian sources concerning the Moon and the planets, be they textual or iconographical, the astronomical, astrological, and religious aspects are intertwined. The term “astral science” covers all forms of Mesopotamian scholarly engagement with celestial entities, including celestial divination and astrology. Modern research on Mesopotamian astral science began in the 19th century. Much research remains to be done, because important sources remain unpublished and new questions have been posed to published sources.

Clay cuneiform tablet. Astronomical; planetary observations (Saturn, Mars and Mercury) mentions year 8 of humbahaldasu , year 2 of Esarhaddon, year 14 of Shamash-shum-ukin, year 1 of Kandalanu and year 7 of Nabopolassar

Late Babylonian mesopotamia Iraq

Excavated by: Hormuzd Rassam

Findspot: Babylon (Iraq

From ca. 3000 BCE onward, Mesopotamians used a calendar with months and years, which indicates that the Moon was studied at that early age. In cuneiform writing, the Sumerian and Akkadian names of the Moongod, Nanna/Sin, are attested since ca. 2500 BCE. The most common Akkadian names of the five planets, Šiḫṭu (Mercury), Dilbat (Venus), Ṣalbatānu (Mars), White Star (Jupiter), and Kayyāmānu (Saturn), are attested first in 1800–1000 BCE. The Moon, the Sun, and the planets were viewed as gods or manifestations of gods. From ca. 1800 BCE onward, the phenomena of the Moon, the Sun, and the planets were studied as signs that were produced by the gods to communicate with humankind.

In the 1st millennium BC we find evidence of a large range of astronomical activity in Assyria and Babylonia.

Clay cuneiform tablet Astronomical planetary observations abbreviated star names

Cultures Late Babylonian Mesopotamia Iraq

This includes: regular and systematic observation; the identification of lunar, solar and planetary periodicities; the development of empirical methods of predicting future astronomical phenomena such as passages of planets by reference stars, lunar and solar eclipses and the dates of first and last visibility and stations of the planets; the development of mathematical methods of calculating lunar and planetary phenomena; the astrological interpretation of celestial events; and the advance prediction of the calendar. Many aspects of Mesopotamian astronomy were transmitted to Greece, India and other cultures, including: the zodiac; the sexagesimal number system; many numerical parameters that underlie the astronomical theories of Ptolemy and other astronomers; whole systems of mathematical astronomy; and, indeed, the very notion that astronomical events can be analysed numerically and predicted.

Library of Ashurbanipal

Nineveh iraq Mesopotamia

Clay tablet, letter, astrological, from Bel-nasir 11 lines of inscription, Late Babylonian Nearly complete astrological report and letter to the king concerning observations of the moon in the appended letter the king is asked to send a physician to Cultures Late Babylonian

Between ca. 600 BCE and 100 CE, Babylonian scholars reported lunar and planetary phenomena in astronomical diaries and related texts. Their purpose was to enable predictions of the reported phenomena with period-based, so-called Goal-Year methods. After the end of the 5th century BCE Babylonian astronomers introduced the zodiac and developed new methods for predicting lunar and planetary phenomena known as mathematical astronomy At about the same time they developed horoscopy and other forms of astrology that use the zodiac, the Moon, the Sun, and the planets to predict events on Earth

Clay cuneiform tablet Astronomical System A lunar ephemeris

Late Babylonian mesopotamia Iraq

Findspot Babylon Iraq

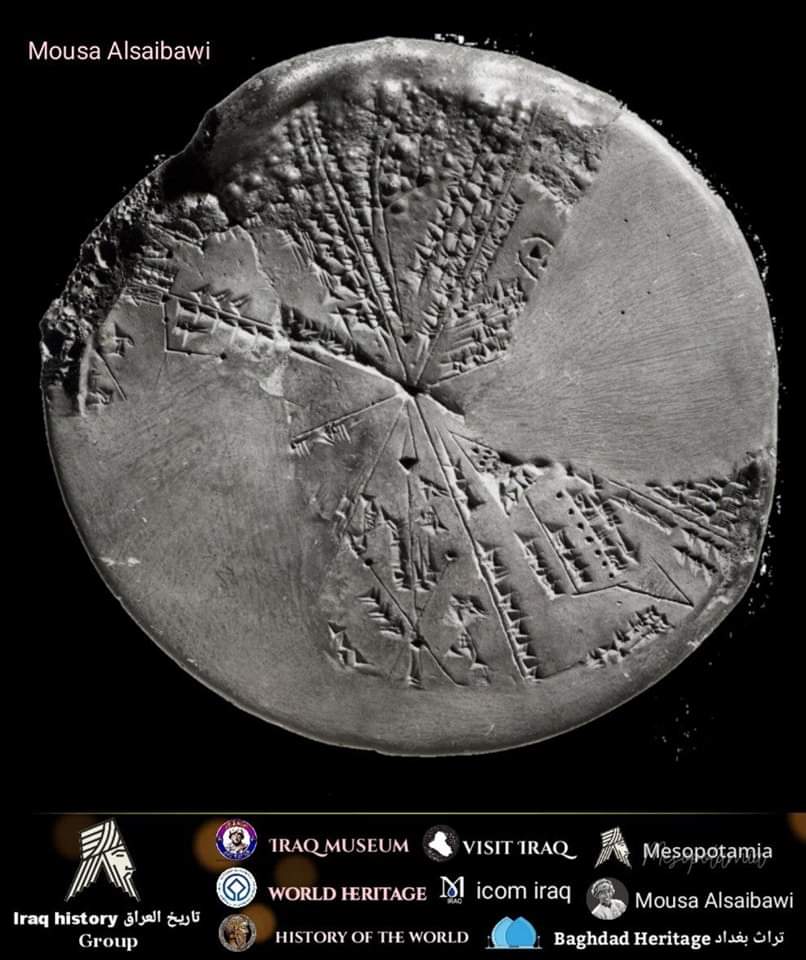

Fragment of a circular clay tablet with depictions of constellations (planisphere) Neo-Assyrian. The reverse is uninscribed Section of a sphere or instrument for astrological calculations The flat side is inscribed with mathematical figures and descrip For comment on the interpretation of the text and identification of the constellations see Koch 1989 Celestial planisphere in this stylised map the sky has been divided into eight sections It represents the night sky of 3-4 January 650 BC over Nineveh iraq The rectangular shape at the top has been identified as the constellation known today as Gemini and the stars contained with an oval shape are the Pleiades The two triangles in the lower right mark the bright stars of Pegasus

Excavator by: Hormuzd Rassam Nineveh iraq Mesopotamia

Title Series Library of Ashurbanipal

astronomical report glossed 14 lines of inscription Neo-Assyrian Complete astrological report to the king concerning observations of the sun, moon and Saturn Associated names Associated with Ashurbanipal

clay tablet from middle astrological refers to constellations. 3 lines of inscription Neo-Assyrian library of Ashurbanipal Mesopotamia iraq 600 – 700 BCE

The concept of the zodiac originated in Babylonian astrology

From Nasa

Clay cuneiform tablet. Astronomical procedure text for Jupiter firing-holes

Mesopotamia Babylon iraq 1500 – 1800 BCE

2019 – 8 -8 Astronomers just stitched together an unprecedented portrait of Jupiter in infrared and realized its Great Red Spot is full of holes

team of researchers from NASA and the University of California, Berkeley combined data from the Hubble Space Telescope, the Juno probe that orbits Jupiter, and the Gemini Observatory on Earth The team released the images alongside a research paper in The Astrophysical Journal on Thursday.2019

Our Sources : NASA

History Begins at Sumer (Philadelphia, 1956), Thirty Nine Firsts in Recorded History, by Samuel Noah Kramer, in 404 searchable pdf pages.

Selected Writings of Samuel Noah Kramer, in 570 bookmarked and searchable pdf pages.

Green، M.W. (1981). “The Construction and Implementation of the Cuneiform Writing System

Samuel Noah Kramer University of Pennsylvania Press, 1972 – History – 130 pages

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1944). Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C. American Philosophical Society. Revised edition: 1961.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1981). History Begins at Sumer: Thirty-Nine Firsts in Man’s Recorded History (3 ed.). University of Pennsylvania Press. I. First edition: 1956 (Twenty-Five Firsts). Second Edition: 1959 (Twenty-Seven Firsts).

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1963). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character Samuel Noah Kramer (PDF). University of Chicago Press.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1967). Cradle of Civilization: Picture-text survey that reconstructs the history, politics, religion and cultural achievements of ancient Sumer, Babylonia and Assyria. Time-Life: Great Ages of Man: A History of the World’s Cultures..

- Wolkstein, Diane; Kramer, Samuel Noah (1983). Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer. New York: Harper & Row.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1988a). In the World of Sumer: An Autobiography. Wayne State University Press

- Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization. Paul Kriwaczek.

Ancient Mesopotamia. Leo Oppenheim.

Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History. University of Chicago.

Mesopotamia 8000-2000 B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

30,000 Years of Art. Editors at Phaidon. - Treasures of the Iraq Museum Faraj Basmachi Ministry of Information, 1976 – Art, Iraqi – 426 pages

- Algaze, Guillermo, 2008 Ancient Mesopotamia at the Dawn of Civilization: the Evolution of an Urban Landscape. University of Chicago Press

- Atlas de la Mésopotamie et du Proche-Orient ancien, Brepols, 1996

- Bottéro, Jean; 1987. (in French) Mésopotamie. L’écriture, la raison et les dieux, Gallimard, coll. « Folio Histoire »,

- Edzard, Dietz Otto; 2004. Geschichte Mesopotamiens. Von den Sumerern bis zu Alexander dem Großen, München,

- Hrouda, Barthel and Rene Pfeilschifter; 2005. Mesopotamien. Die antiken Kulturen zwischen Euphrat und Tigris. München 2005 (4. Aufl.),

- Joannès, Francis; 2001. Dictionnaire de la civilisation mésopotamienne, Robert Laffont.

- Korn, Wolfgang; 2004. Mesopotamien – Wiege der Zivilisation. 6000 Jahre Hochkulturen an Euphrat und Tigris, Stuttgart,

- Matthews, Roger; 2005. The early prehistory of Mesopotamia – 500,000 to 4,500 BC, Turnhout 2005,

- Oppenheim, A. Leo; 1964. Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a dead civilization. The University of Chicago Press: Chicago and London. Revised edition completed by Erica Reiner, 1977.

- Pollock, Susan; 1999. Ancient Mesopotamia: the Eden that never was. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- Postgate, J. Nicholas; 1992. Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the dawn of history. Routledge: London and New York.

- Roux, Georges; 1964. Ancient Iraq, Penguin Books.

- Silver, Morris; 2007. Redistribution and Markets in the Economy of Ancient Mesopotamia: Updating Polanyi, Antiguo Oriente

- Pingree, David (1998). “Legacies in Astronomy and Celestial Omens”. In Dalley, Stephanie (ed.). The Legacy of Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press.

- Stager, L. E. (1996). “The fury of Babylon: Ashkelon and the archaeology of destruction”. Biblical Archaeology Review. 22 (1).

- Stol, Marten (1993). Epilepsy in Babylonia. Brill Publishers.

- Louvre Museum

- Vatican Museums

- British Museum

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Rijksmuseum

- Ashmolean Museum

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Field Museum of Natural History