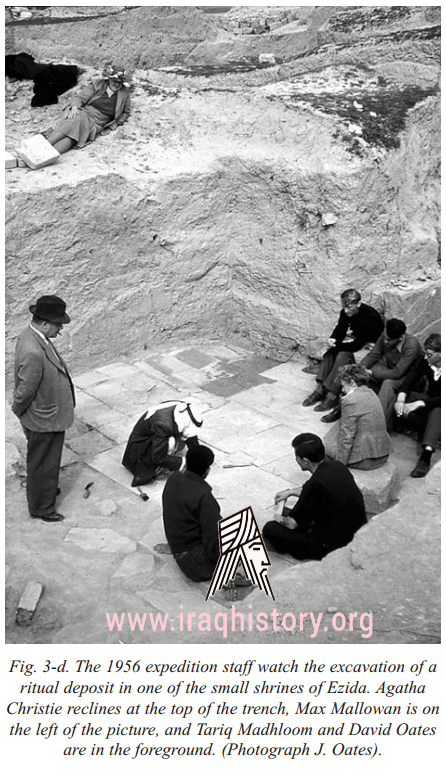

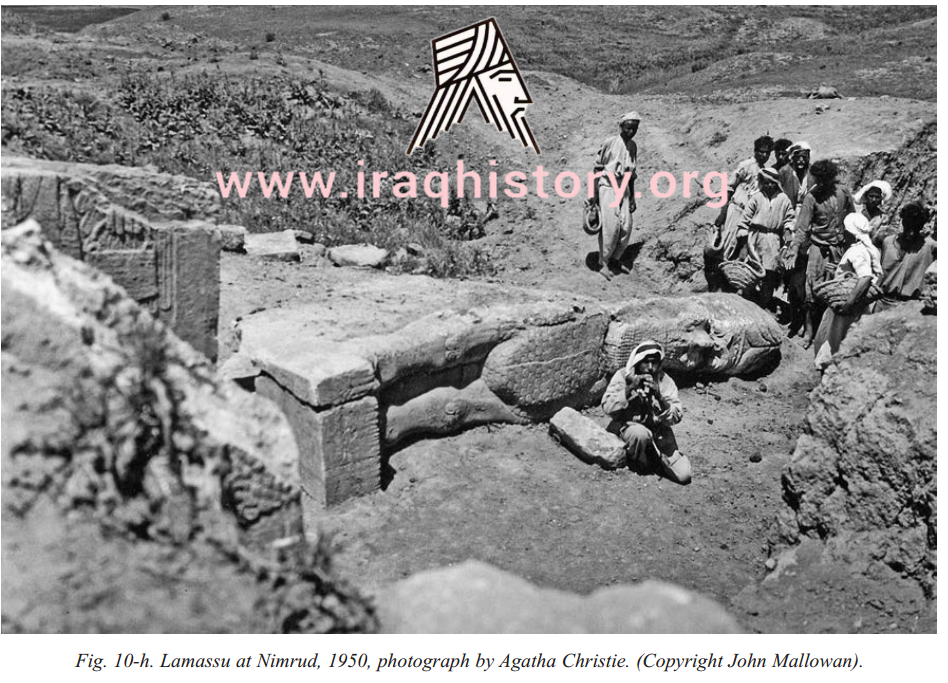

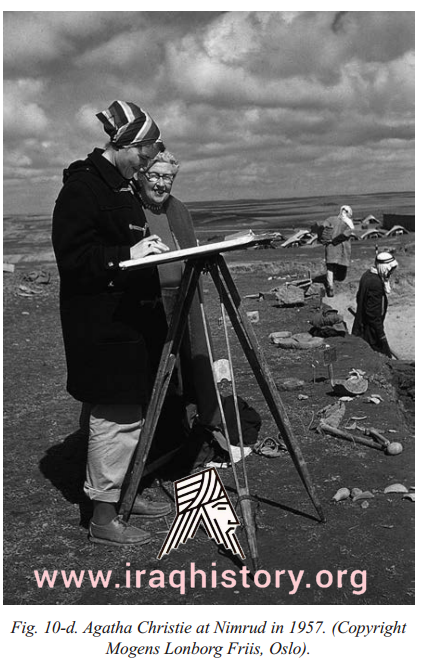

Initial excavations at Nimrud were conducted by Austen Henry Layard, working from 1845 to 1847 and from 1849 until 1851.Following Layard’s departure, the work was handed over to Hormuzd Rassam in 1853-54 and then William Loftus in 1854–55.[After George Smith briefly worked the site in 1873 and Rassam returned there from 1877 to 1879, Nimrud was left untouched for almost 60 years. A British School of Archaeology in Iraq team led by Max Mallowan resumed digging at Nimrud in 1949; these excavations resulted in the discovery of the 244 Nimrud Letters. The work continued until 1963 with David Oates becoming director in 1958 followed by Julian Orchard in 1963.Easarhaddon cylinder from fort Shalmaneser at Nimrud. It was found in the city of Nimrud and was housed in the Iraq Museum, Baghdad. Erbil Civilization Museum, Iraq Subsequent work was by the Directorate of Antiquities of the Republic of Iraq (1956, 1959–60, 1969–78 and 1982–92) the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology University of Warsaw directed by Janusz Meuszyński (1974–76) Paolo Fiorina (1987–89) with the Centro Ricerche Archeologiche e Scavi di Torino who concentrated mainly on Fort Shalmaneser, and John Curtis (1989).[26] In 1974 to his untimely death in 1976 Janusz Meuszyński, the director of the Polish project, with the permission of the Iraqi excavation team, had the whole site documented on film—in slide film and black-and-white print film.

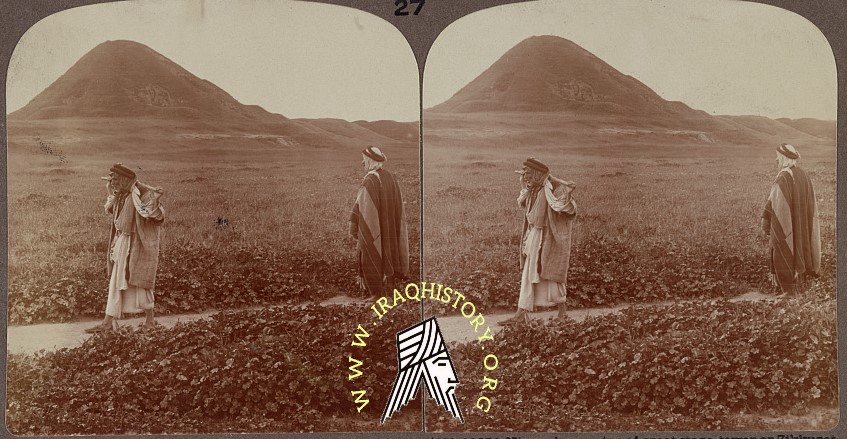

Nimrud, remains of great stage-tower or Zikkurat

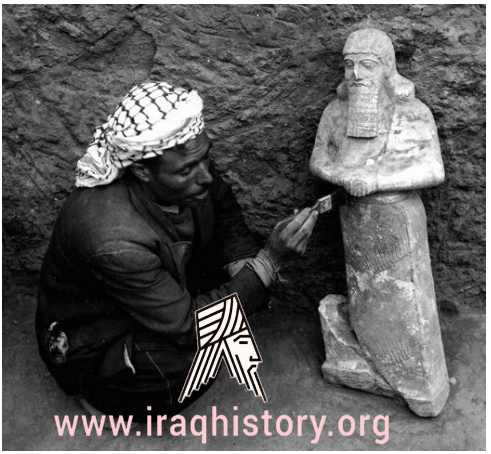

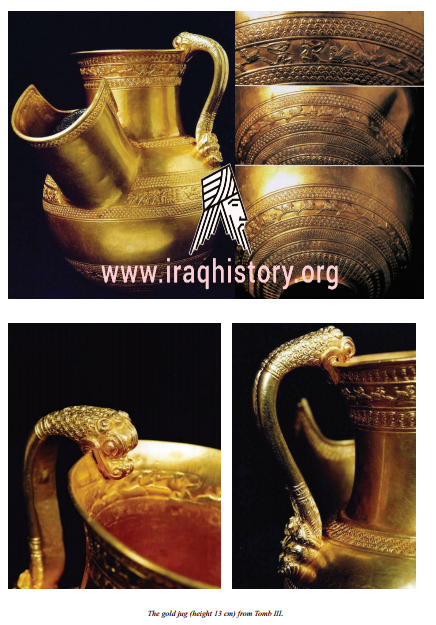

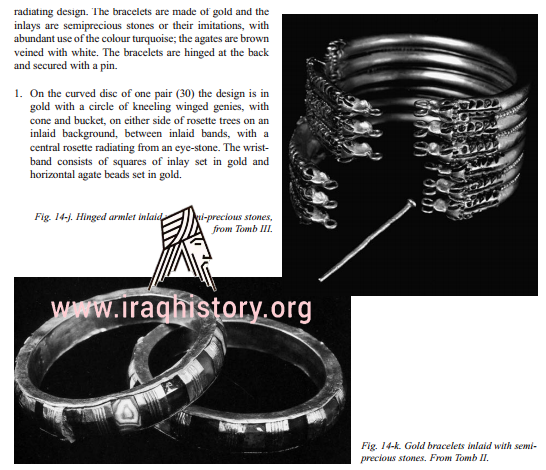

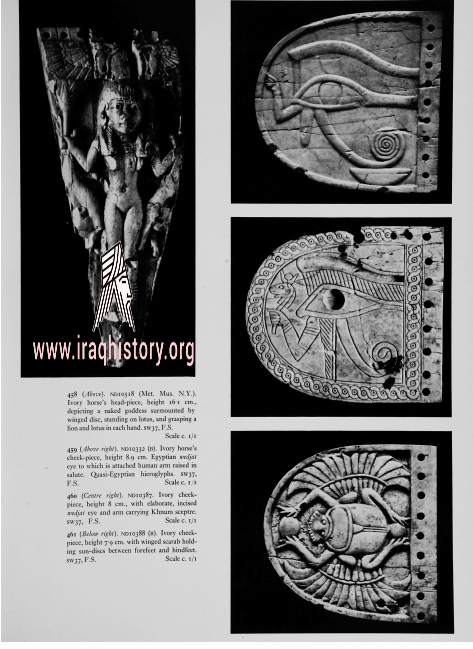

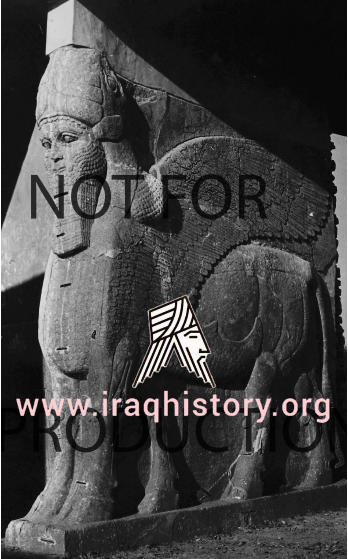

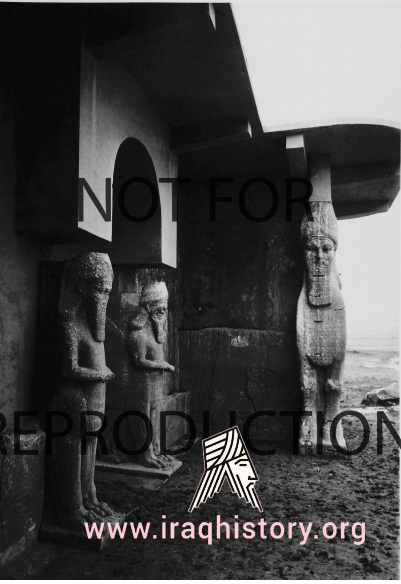

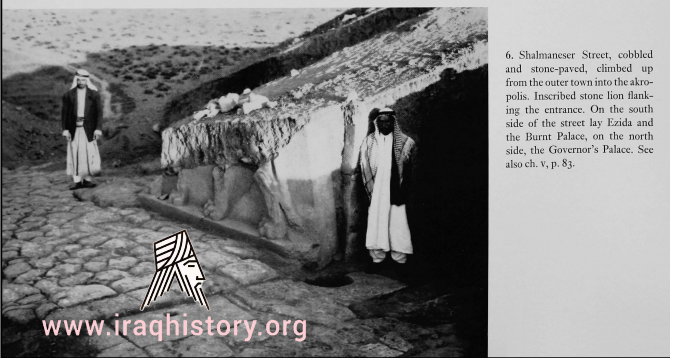

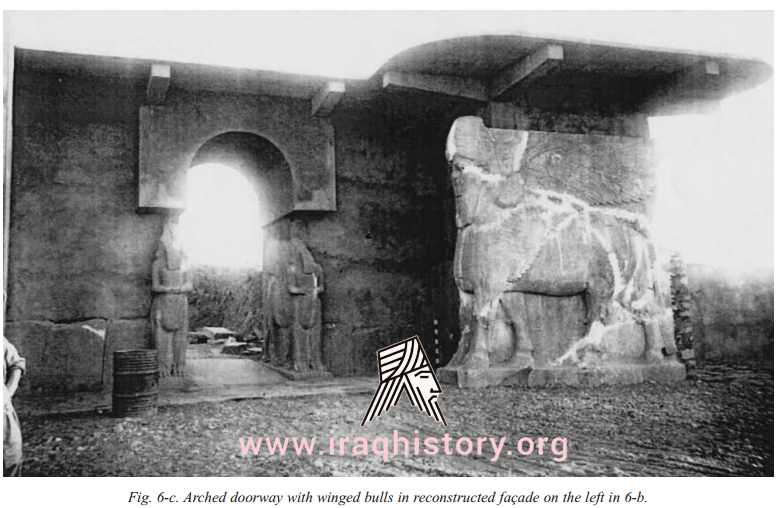

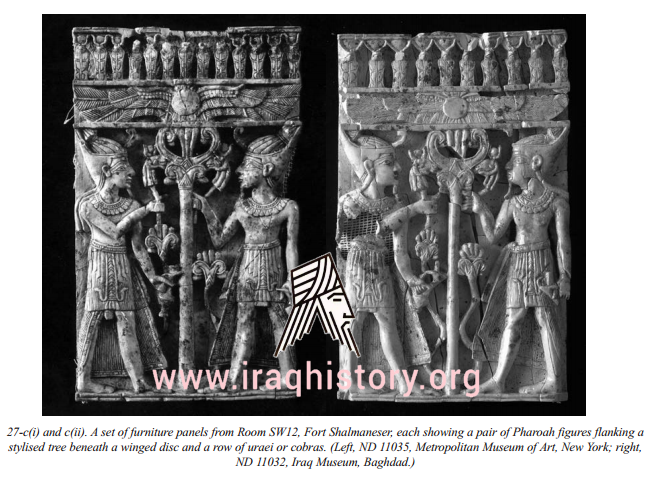

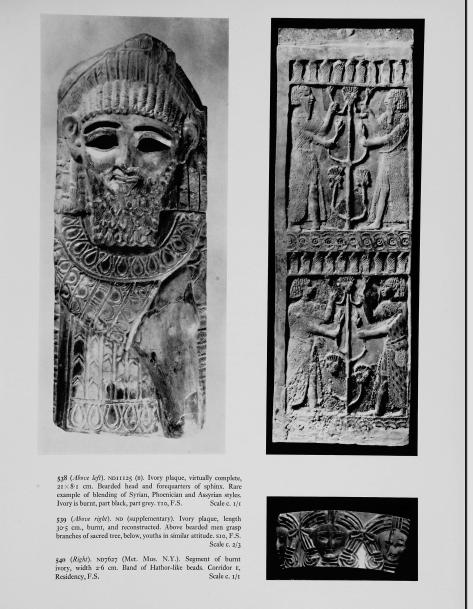

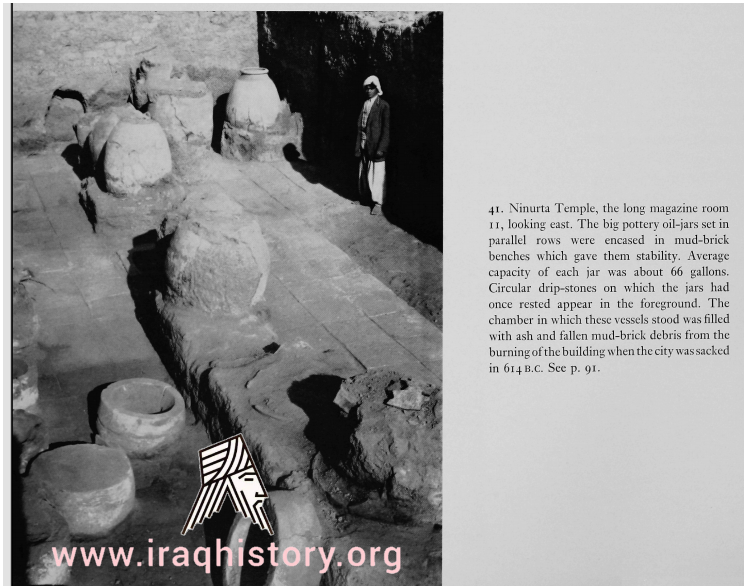

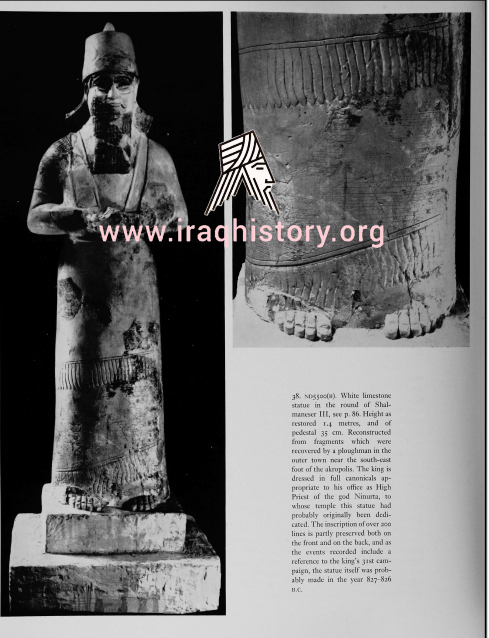

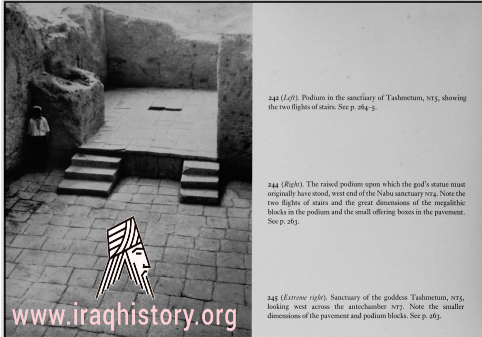

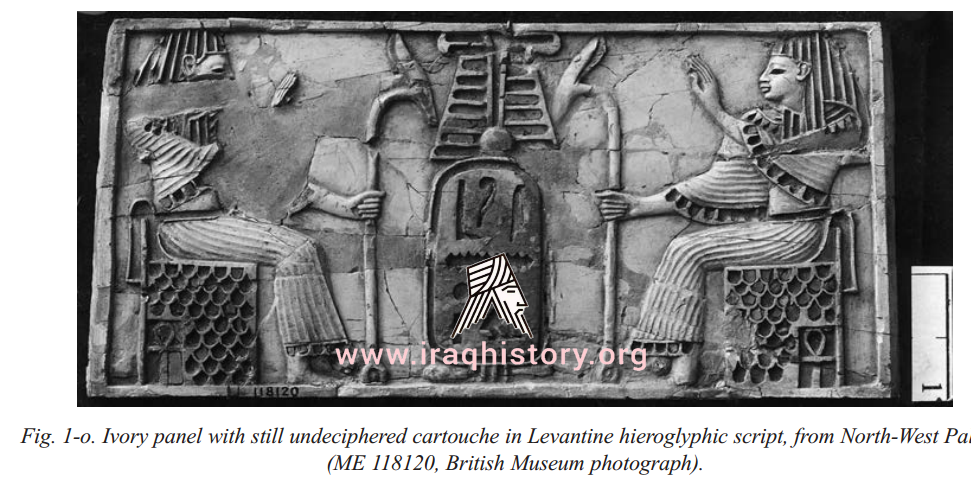

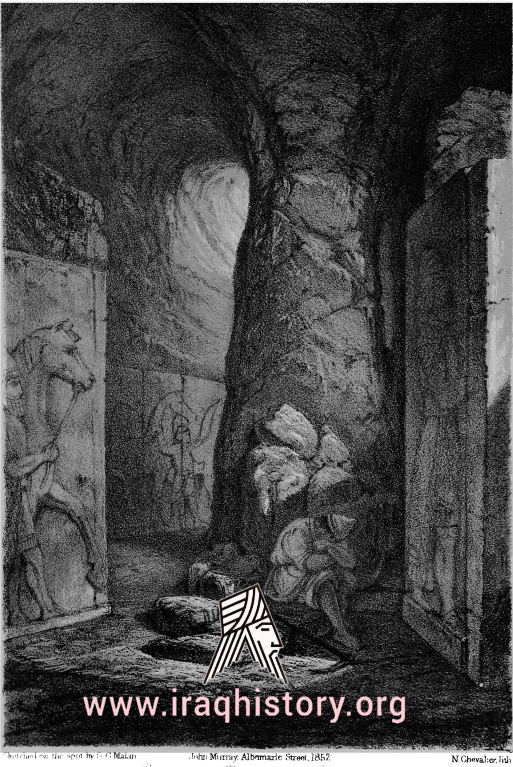

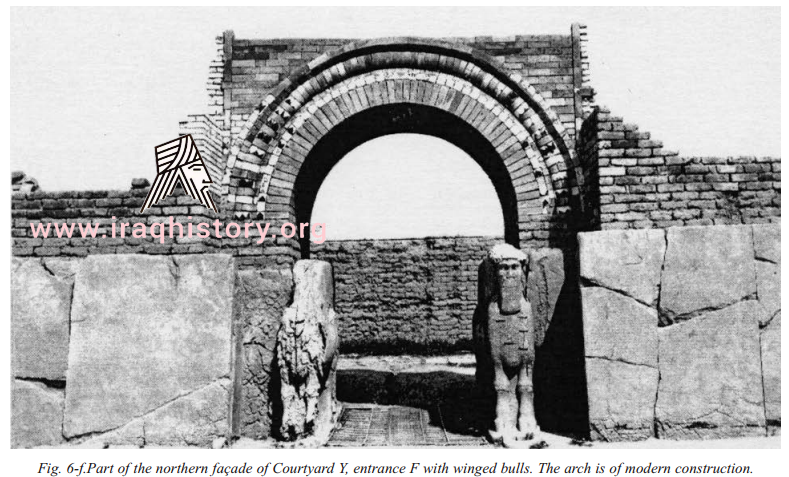

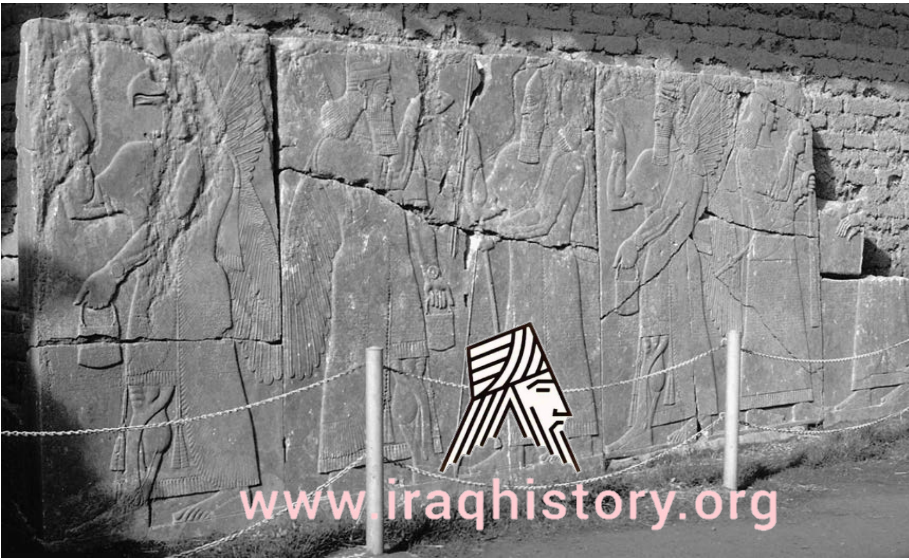

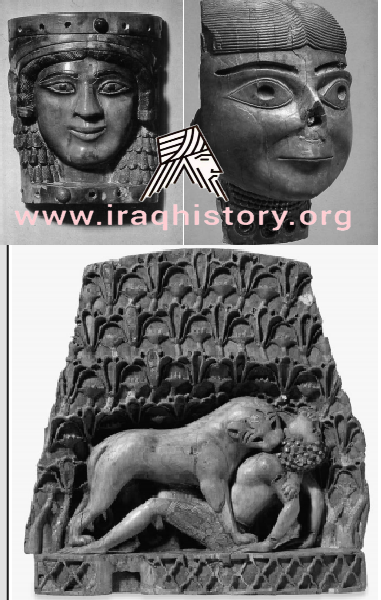

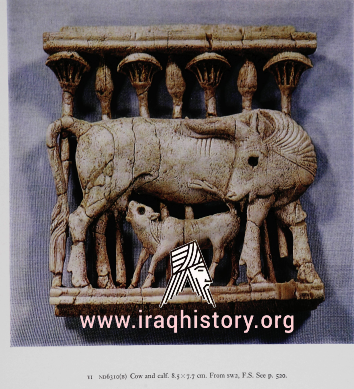

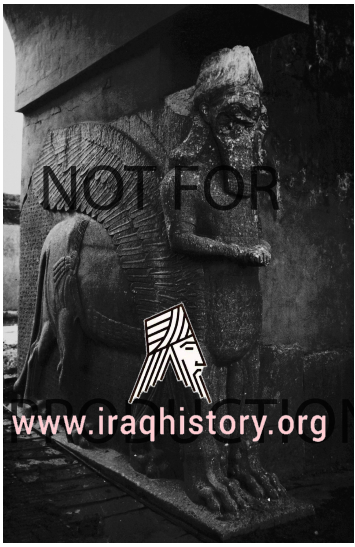

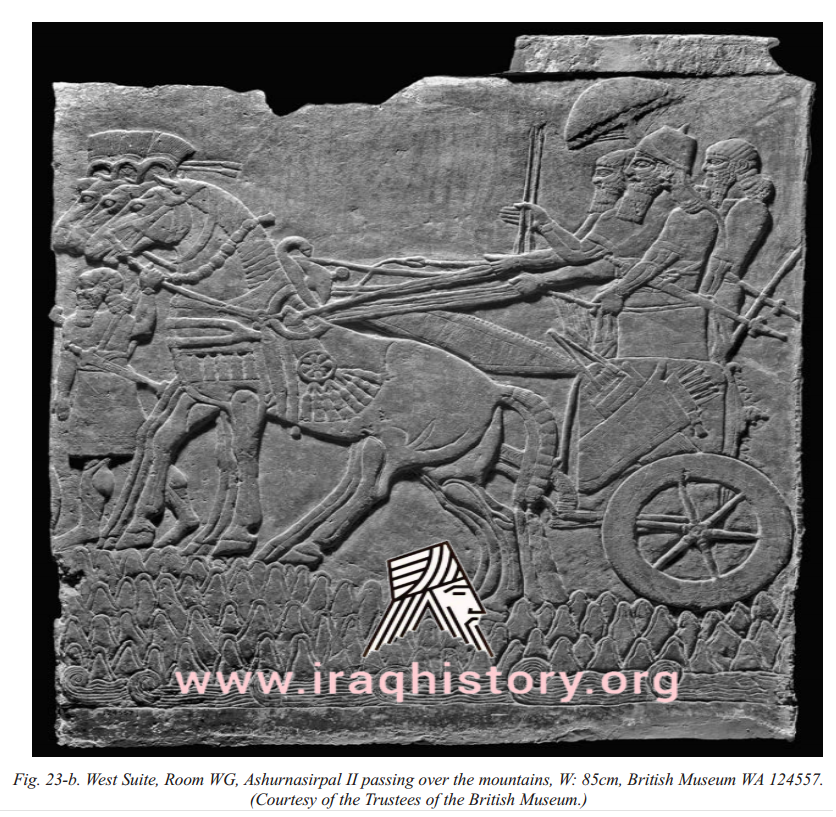

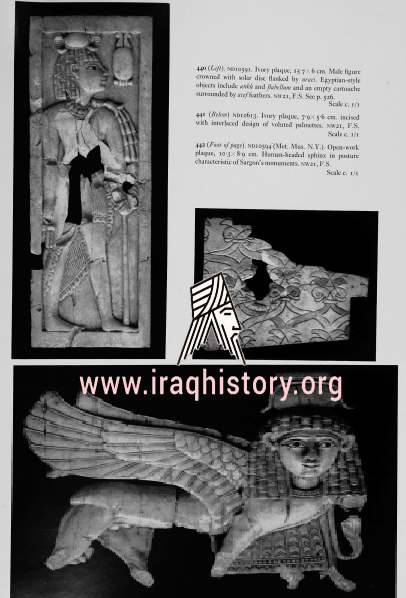

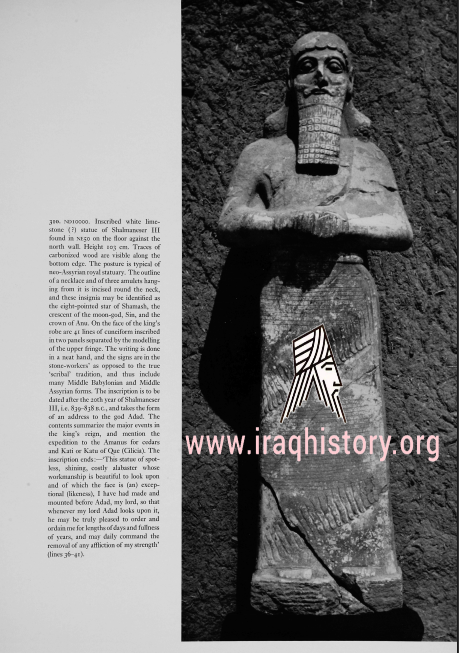

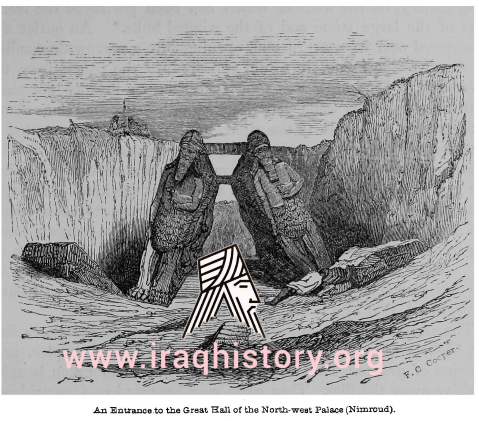

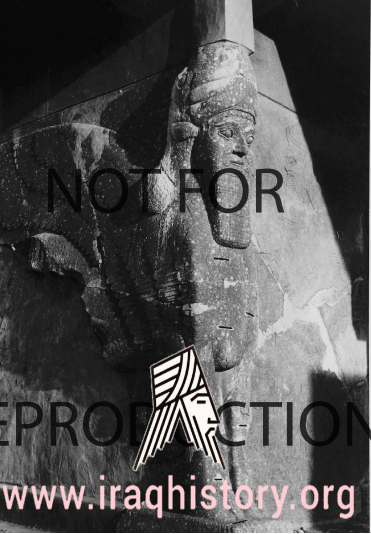

Every relief that remained in situ, as well as the fallen, broken pieces that were distributed in the rooms across the site were photographed. Meuszyński also arranged with the architect of his project, Richard P. Sobolewski, to survey the site and record it in plan and in elevation. As a result, the entire relief compositions were reconstructed, taking into account the presumed location of the fragments that were scattered around the world Excavations revealed remarkable bas-reliefs, ivories, and sculptures. A statue of Ashurnasirpal II was found in an excellent state of preservation, as were colossal winged man-headed lions weighing 10 short tons (9.1 t) to 30 short tons each guarding the palace entrance. The large number of inscriptions dealing with king Ashurnasirpal II provide more details about him and his reign than are known for any other ruler of this epoch. The palaces of Ashurnasirpal II, Shalmaneser III, and Tiglath-Pileser III have been located. Portions of the site have been also been identified as temples to Ninurta and Enlil, a building assigned to Nabu, the god of writing and the arts, and as extensive fortifications. Remains of the Nabu temple in 2008 In 1988, the Iraqi Department of Antiquities discovered four queens’ tombs at the site.

The mound of Nimrud

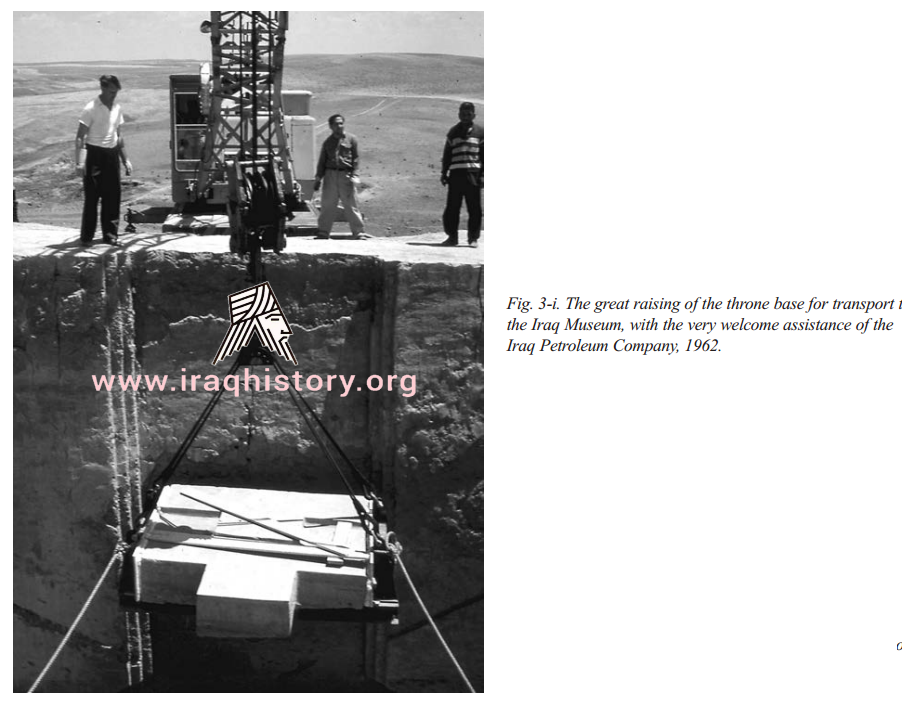

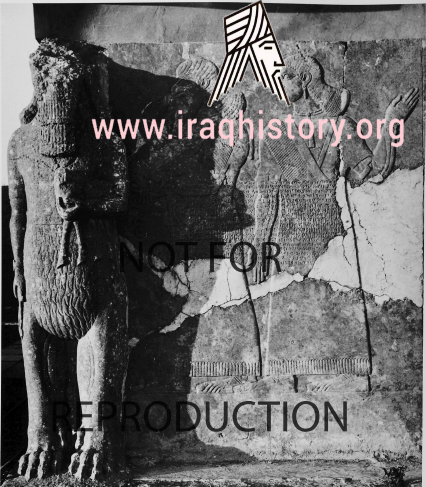

Nimrud has been one of the main sources of Assyrian sculpture, including the famous palace reliefs. Layard discovered more than half a dozen pairs of colossal guardian figures guarding palace entrances and doorways. These are lamassu, statues with a male human head, the body of a lion or bull, and wings. They have heads carved in the round, but the body at the side is in relief.[30] They weigh up to 27 tonnes (30 short tons). In 1847 Layard brought two of the colossi weighing 9 tonnes (10 short tons) each including one lion and one bull to London. After 18 months and several near disasters he succeeded in bringing them to the British Museum. This involved loading them onto a wheeled cart. They were lowered with a complex system of pulleys and levers operated by dozens of men. The cart was towed by 300 men. He initially tried to hook up the cart to a team of buffalo and have them haul it. However the buffalo refused to move. Then they were loaded onto a barge which required 600 goatskins and sheepskins to keep it afloat. After arriving in London a ramp was built to haul them up the steps and into the museum on rollers.