It was the largest city in the world for approximately fifty years[2] until the year 612 BC when, after a bitter period of civil war in Assyria, it was sacked by a coalition of its former subject peoples including the Babylonians, Medes, Persians, Scythians and Cimmerians. The city was never again a political or administrative centre, but by Late Antiquity it was the seat of a Christian bishop.[citation needed] It declined relative to Mosul during the Middle Ages and was mostly abandoned by the 13th century AD.

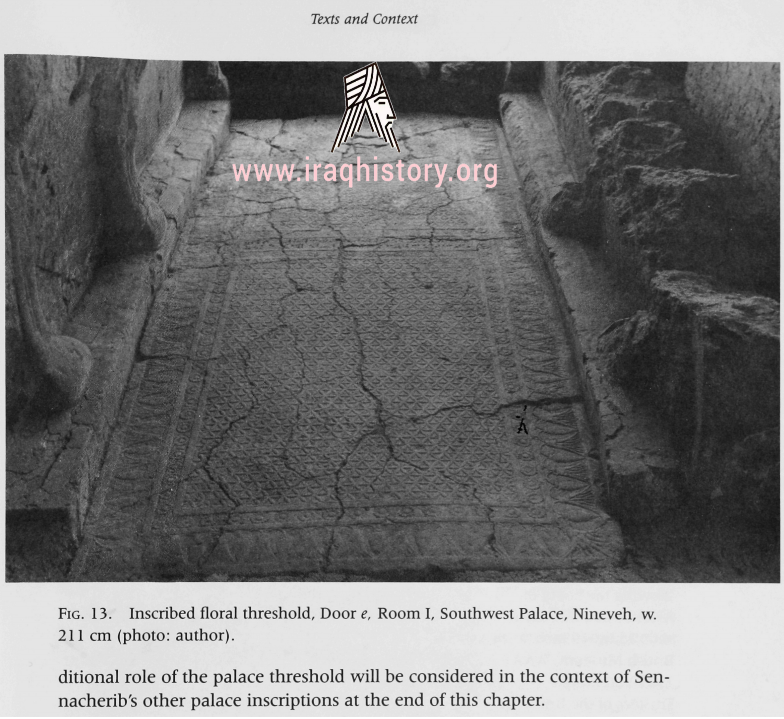

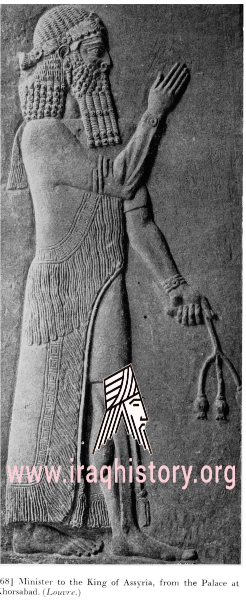

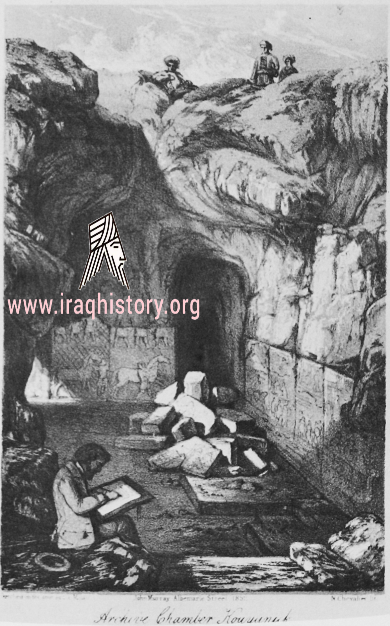

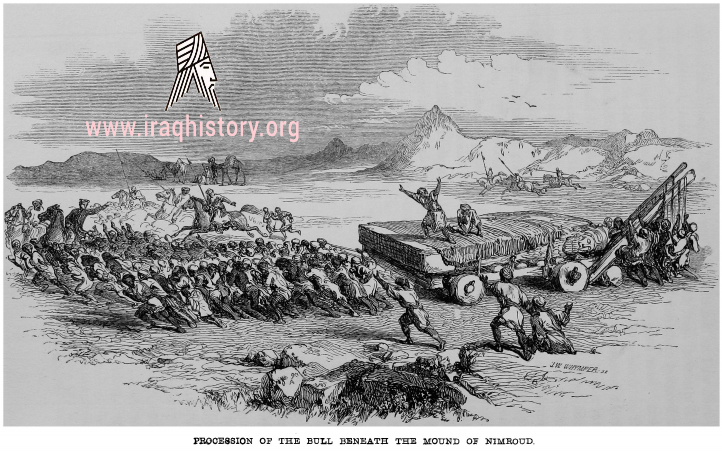

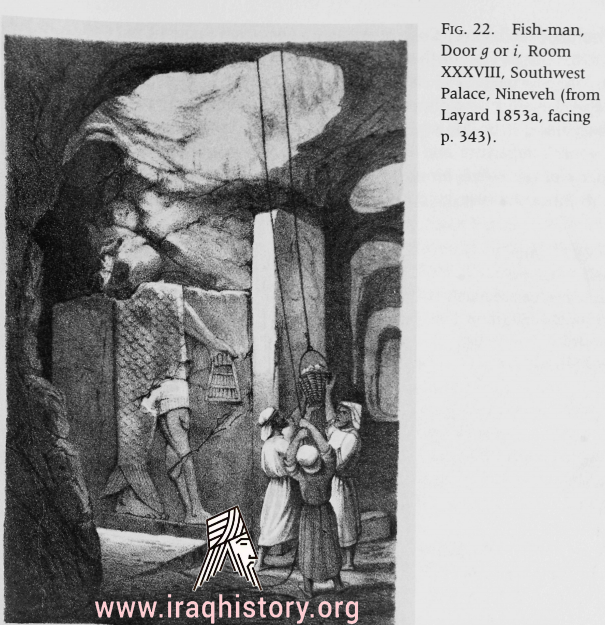

In the 1st millennium BC, Nineveh officially became the capital of the Assyrian Empire and remained so until its fall in 612 BC. Visited by Claudius James Rich in 1820 and briefly explored in 1842 by Paul-Émile Botta, this immense site was excavated mainly by Austen Henry Layard beginning in 1847, assisted by Hormuzd Rassam. Other British archaeologists also worked on the site from the 1870s until the early 20th century: George Smith, Ernest Alfred Wallis Budge, Leonard William King and Reginald Campbell Thompson.

From the 1950s onwards, an Iraqi team excavated at Kuyunjik and Nebi Yunus. They worked under the direction of M. A. Mustafa from 1951 to 1958, Tariq Madhlum from 1967 to 1971, Manhal Jabur in 1980, and Abd al-Sattar in 1987. At the end of the 1980s, the University of Berkeley excavated the lower city under the direction of David Stronach. In recent years, work at Nineveh has been resumed by an Italian team directed by Nicolo Marchetti and a German team directed by Peter Miglus

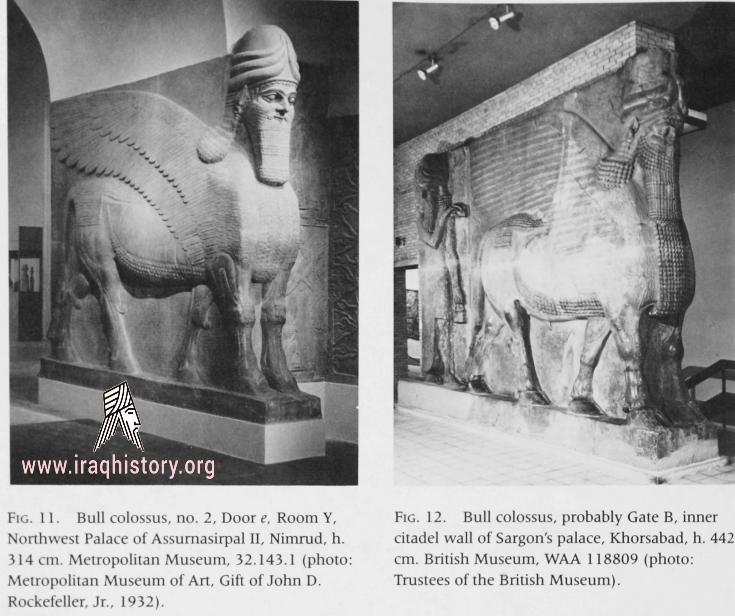

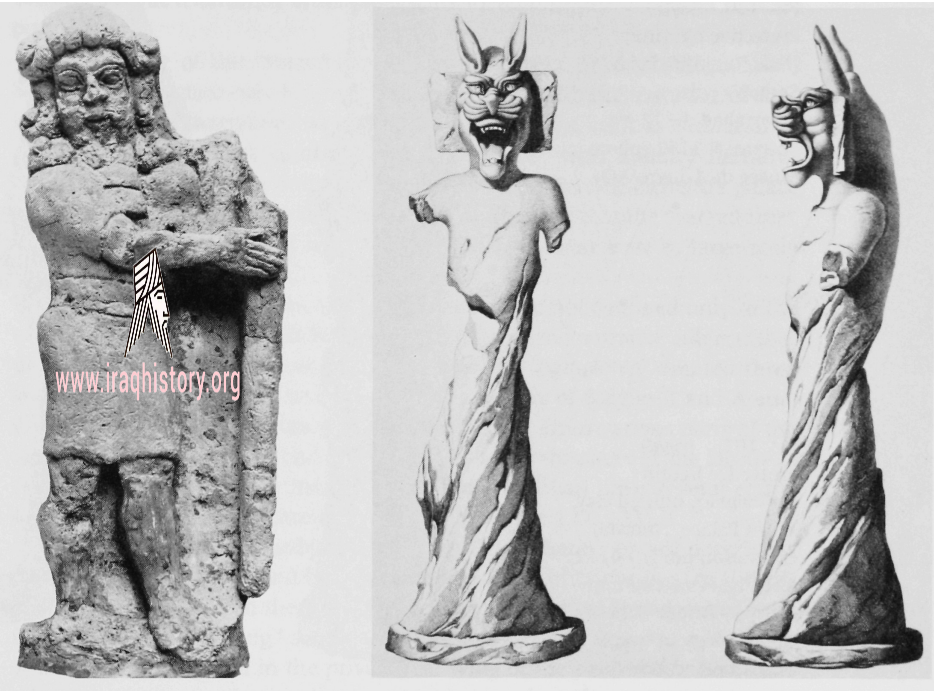

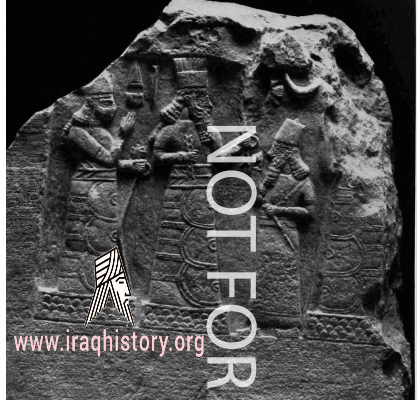

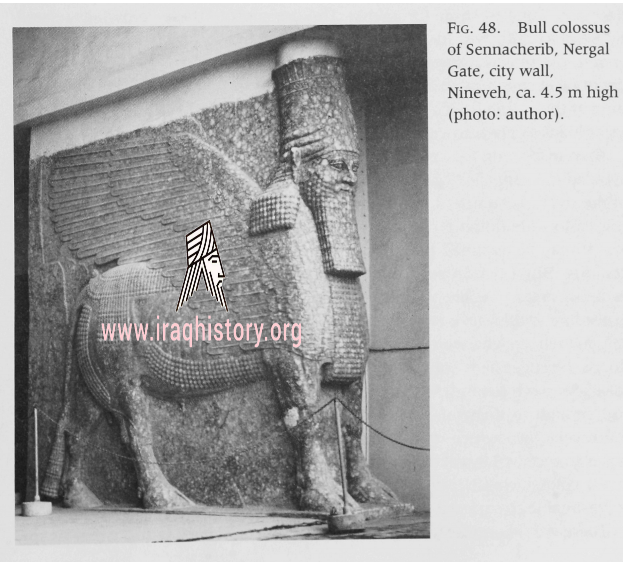

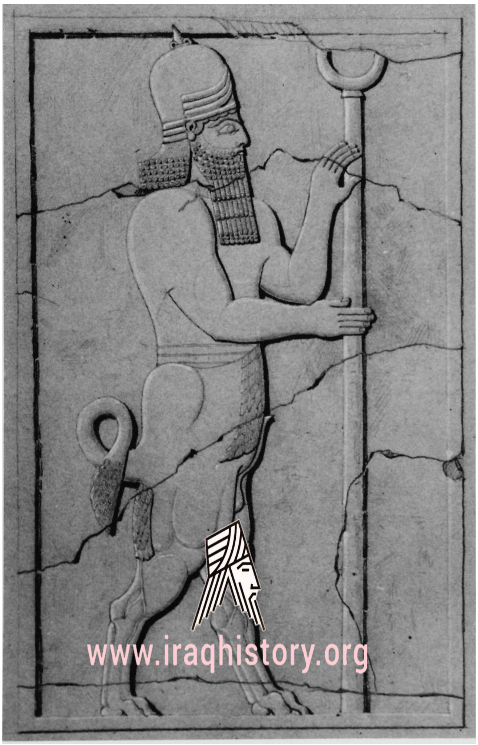

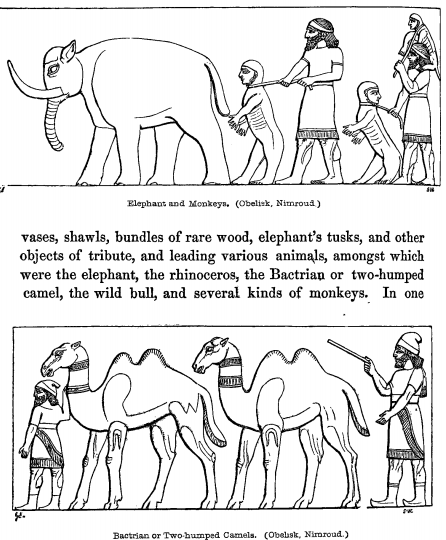

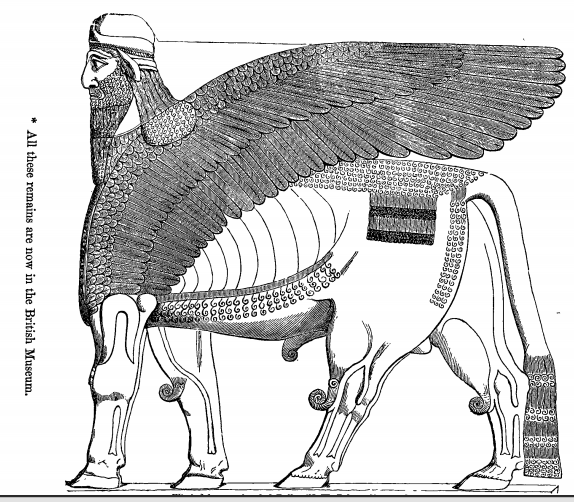

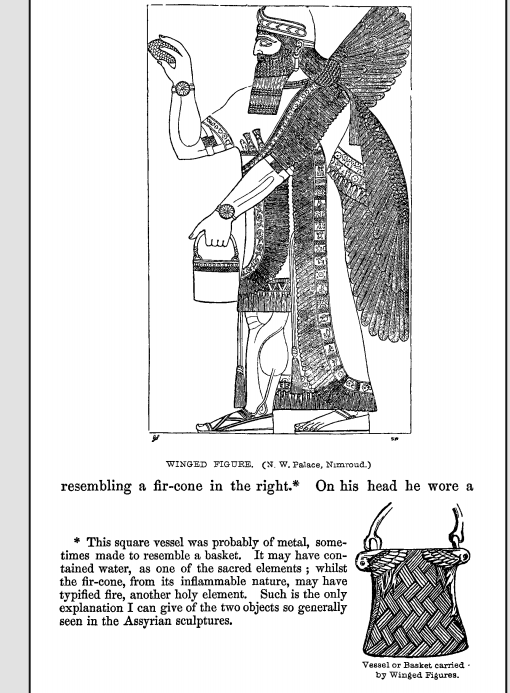

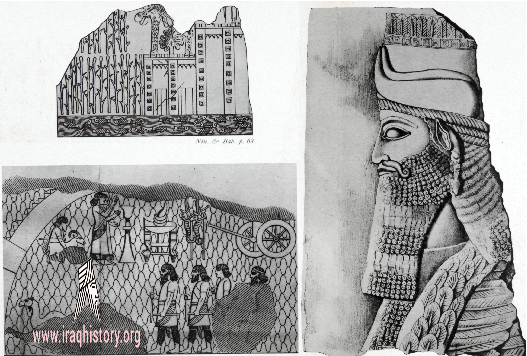

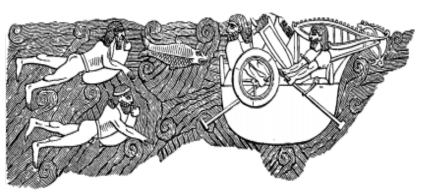

This small pattern carved from stone represents a type of column base that was used in Assyrian palaces during the seventh century BC. This ornate column base represents a sphinx (with four legs) and without a beard with a flat hat and horned Found in Nineveh in 1875 by George Smith and believed to represent a winged cow with a human head/preserved in the British Museum.